The perspective article is online: https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0235507

arxiv preprint: https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.15791

The perspective article is online: https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0235507

arxiv preprint: https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.15791

The title of this blog is the closing line of an autobiographical essay written by John Hopfield (pictured above), one of the physics Nobel laureates today: “for foundational discoveries and inventions that enable machine learning with artificial neural networks.”

In this essay, he retraces his trajectory across various sub-disciplines of physics and how he eventually used his knowledge of physics to work on a problem in neurobiology that further connects to machine learning.

The title of the essay is provocative(see below) but worth reading to understand how physics has evolved over the years and its profound impact on various disciplines.

Reference: Hopfield, John J. “Whatever Happened to Solid State Physics?” Annual Review of Condensed Matter Physics 5, no. Volume 5, 2014 (March 10, 2014): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-conmatphys-031113-133924.

Thanks to Gautam Menon for bringing the essay to my notice.

By the way, Hopfield and Deepak Dhar shared the 2022 Boltzmann medal, and after the award, he gave a wonderful online talk at IMSc, Chennai. Thanks to Arnab Pal of IMSc for bringing this to my notice on X.

Let me end this post quoting Hopfield from the mentioned essay:

What is physics? To me—growing up with a father and mother who were both physicists—physics was not subject matter. The atom, the troposphere, the nucleus, a piece of glass, the washing machine, my bicycle, the phonograph, a magnet—these were all incidentally the subject matter. The central idea was that the world is understandable, that you should be able to take anything apart, understand the relationships between its constituents, do experiments, and on that basis be able to develop a quantitative understanding of its behavior. Physics was a point of view that the world around us is, with effort, ingenuity, and adequate resources, understandable in a predictive and reasonably quantitative fashion. Being a physicist is a dedication to the quest for this kind of understanding.

Let that quest never die!

We have an Arxiv preprint on how a mixture of colloids (thermally active + passive particles in water) can lead to the emergence of revolution dynamics in an optical ring trap (dotted line). Super effort by our lab members Rahul Chand and Ashutosh Shukla.

Interestingly, the revolution emerges only when an active and a passive colloid are combined (not as individuals) in a ring potential (dotted line)

the direction (clock or anti-clockwise) of the revolution depends on the relative placement of the colloids in the trap

This revolution can be further used to propel a third active colloid

There are many more details in the paper. Check it out: https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.16792

Over the years, I have been giving student assignments to write about their questions (rather than answers to my Qs).

Snapshot of email to my class below.

I have found some gems in the process and importantly reduces the ‘burden’ of single right answers. Student feedback on this process has been positive.

Even in the ChatGPT era, it is the quality of Qs that determines the answer, and in this assignment, students are free to choose their Qs as per their interest and experience connected to what I teach…something harder for ChatGPT to grasp (as of now).

Interesting times ahead.

Recently, I wrote a blog on Graviton-like modes in solids.

There is a nice report from the Columbia Quantum Initiative on the Nature paper.

It highlights the role of Aron (a key author in the paper, who passed away in 2022) and his legacy.

Undoubtedly, the graviton-like connection has created a buzz. As the above report mentions, it has also taken a lot of time and effort on the part of the authors to measure it.

Thanks to my colleague Surjeet Singh, I also learnt about the importance of heterostructures in this work and that authors do not oversell the connection to gravitons in the paper.

For me, as an outsider to the field(s), a few questions remain:

It would be great to know the answers, hopefully, in the coming days.

Recently, there has been a buzz about a Nature paper titled Evidence for chiral graviton modes in fractional quantum Hall liquids. There has been some media reportage on the paper too.

The paper makes interesting claim on observation of ‘chiral graviton modes’ in certain ultra-cooled semiconductors (Gallium Arsenide – famously called GaAs). The cooled temperature is quite low (~50 mK), which is impressive, and the chirality of the mode is unveiled using polarization-resolved Raman scattering. The observation of this so-called ‘Graviton modes’ is essentially a quasiparticle excitation, and has created some buzz. In my opinion, graviton-like behavior is a bit of an exaggeration.

Anyway, this paper has set an interesting discussion among my colleagues (condensed matter and high energy physics) in our department. To add to their discussion, I wrote on 2 points (and an inference) from optics perspective, which I am sharing below :

2. The last author of this paper, Aron Pinczuk, was a well-known expert in light scattering in solids. He was an Argentinian-American professor at Columbia University, and passed away in 2022.

He and the legendary Manuel Cardona were instrumental (pun intended) in laying the foundation for using inelastic light scattering methods in solids. The first edition of the series “Light Scattering in Solids”, written in 1976, has Pincuk discussing the very measurement scheme used in the paper (see picture).

My initial inference on the paper : This is an old Argentinan wine of quasiparticles in a new GaAs bottle at ultra-low temperature….and NATURE is selling it as champagne de graviton made in China !

Gamow, George. 1966. Thirty Years That Shook Physics: The Story of Quantum Theory.

An excerpt from the book mentioned above:

“Planck was a typical German professor of his time, serious and probably pedantic, but not without a warm human feeling, which is evidenced in his correspondence with Arnold Sommerfeld who, following the work of Niels Bohr, was applying the Quantum Theory to the structure of the atom. Referring to the quantum as Planck’s notion, Sommerfeld in a letter to him wrote:

You cultivate the virgin soil,

Where picking flowers was my only toil.and to this answered Planck:

You picked flowers—well, so have I.

Let them be, then, combined;

Let us exchange our flowers fair,

And in the brightest wreath them bind.”

Who thought these scientists were so poetic!

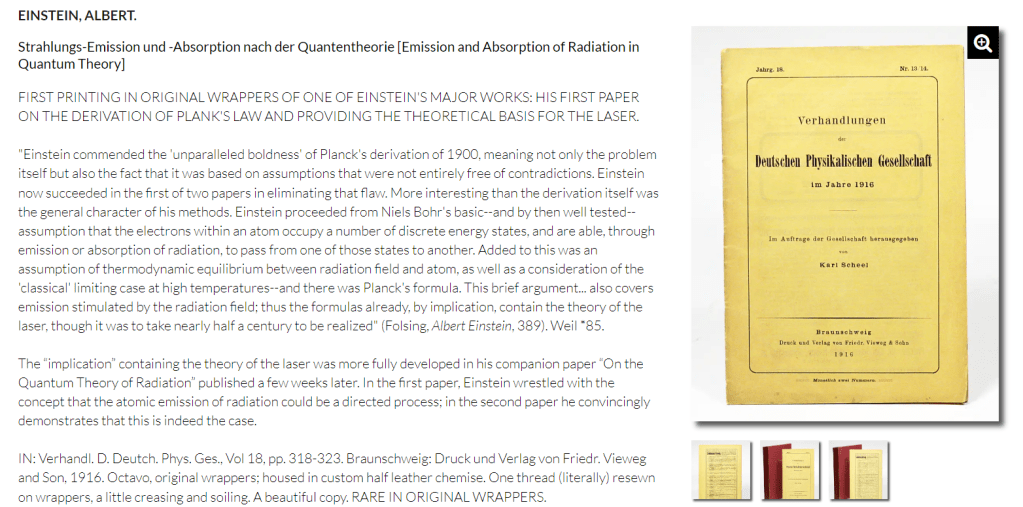

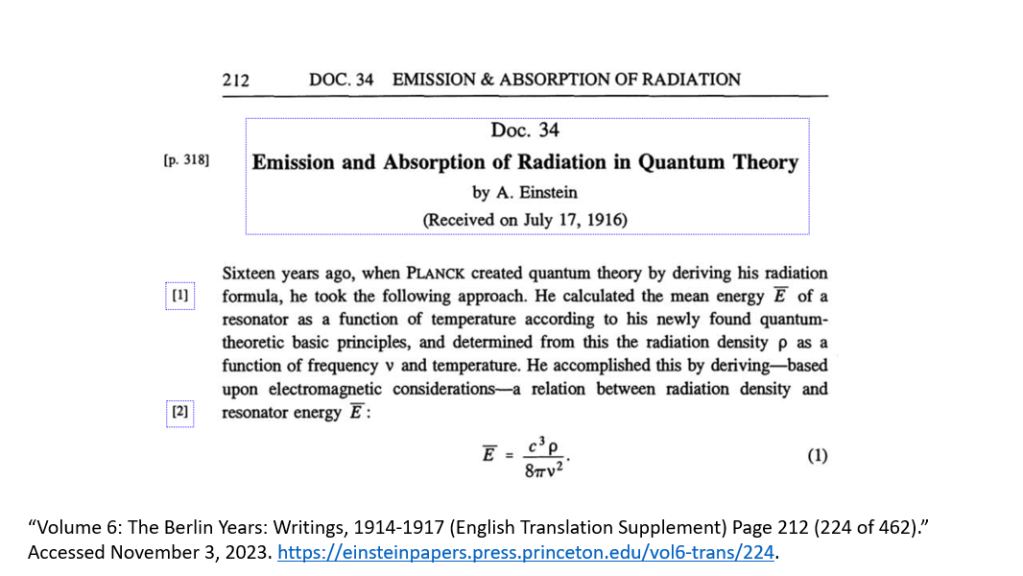

Today, I will be teaching the origins of LASERs in my optics class. Some of the content may interest science enthusiasts here. I present some snapshots from my notes. As expected, it starts with Einstein introducing his A and B coefficients and the stimulated emission.

He introduced them in a paper written in German: Einstein, A. (1916). “Strahlungs-Emission und -Absorption nach der Quantentheorie”. Verhandlungen der Deutschen Physikalischen Gesellschaft. 18: 318–323.

The English translation of the paper: “Volume 6: The Berlin Years: Writings, 1914-1917 (English Translation Supplement) Page 212 (224 of 462).” Accessed November 3, 2023. https://einsteinpapers.press.princeton.edu/vol6-trans/224.

Under thermodynamic equilibrium, the detailed balance gives us the connection between the coefficients…and amplification and stimulated emission of radiation become a measurable prospect.

The pic shows the leading characters behind the invention of the Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation (LASER) Charles Townes was the intellectual pioneer behind microwave variety… and Maiman….the freak behind the optical version..

The history of the invention is fascinating and dramatic. I did a podcast on this a few months ago. Check it out..

Oliver Heaviside

18 May 1850 – 3 February 1925

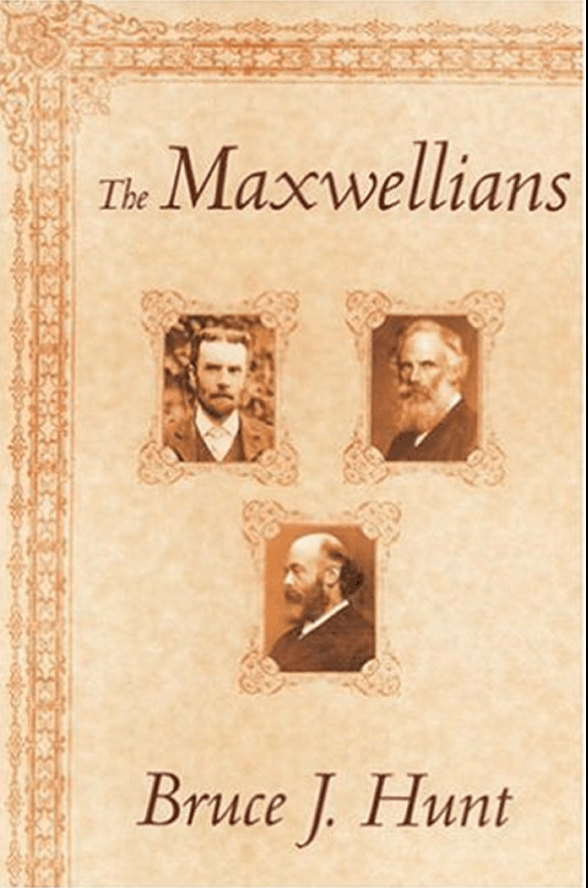

Among the books and discussion on this topic, I found this book by science historian Bruce Hunt to be very interesting. He identifies 3 plus 1 people who extensively developed Maxwell’s electromagnetic theory and presented in a way that the world could understand its significance. They were G. F. FitzGerald, Oliver Heaviside, Oliver Lodge and to a certain extent – Heinrich Hertz.

The foreword of this excellent book was written by a well known historian of science L. Peerce Williams and he sums the situation in which the theory was developed :

“Like Newton’s Principia, Maxwell’s Treatise did not immediately convince

the scientific community. The concepts in it were strange and the

mathematics was clumsy and involved. Most of the experimental basis

was drawn from the researches of Michael Faraday, whose results were

undeniable, but whose ideas seemed bizarre to the orthodox physicist.

The British had, more or less, become accustomed to Faraday’s “vision,”

but continental physicists, while accepting the new facts that poured

from his laboratory, rejected his conceptual structures. One of Maxwell’s

purposes in writing his treatise was to put Faraday’s ideas into the language

of mathematical physics precisely so that orthodox physicists

would be persuaded of their importance.

Maxwell died in 1879, midway through preparing a second edition of

the Treatise. At that time, he had convinced only a very few of his fellow

countrymen and none of his continental colleagues. That task now fell to

his disciples.

The story that Bruce Hunt tells in this volume is the story of the ways

in which Maxwell’s ideas were picked up in Great Britain, modified,

organized, and reworked mathematically so that the Treatise as a whole

and Maxwell’s concepts were clarified and made palatable, indeed irresistible,

to the physicists of the late nineteenth century. The men who

accomplished this, G. F. FitzGerald, Oliver Heaviside, Oliver Lodge, and

others, make up the group that Hunt calls the “Maxwellians.” Their relations

with one another and with Maxwell’s works make for a fascinating

study of the ways in which new and revolutionary scientific ideas move

from the periphery of scientific thought to the very center. In the process,

Professor Hunt also, by extensive use of manuscript sources, examines

the genesis of some of the more important ideas that fed into and

led to the scientific revolution of the twentieth century.“