Welcome to the podcast, Pratidhavani – Humanizing Science

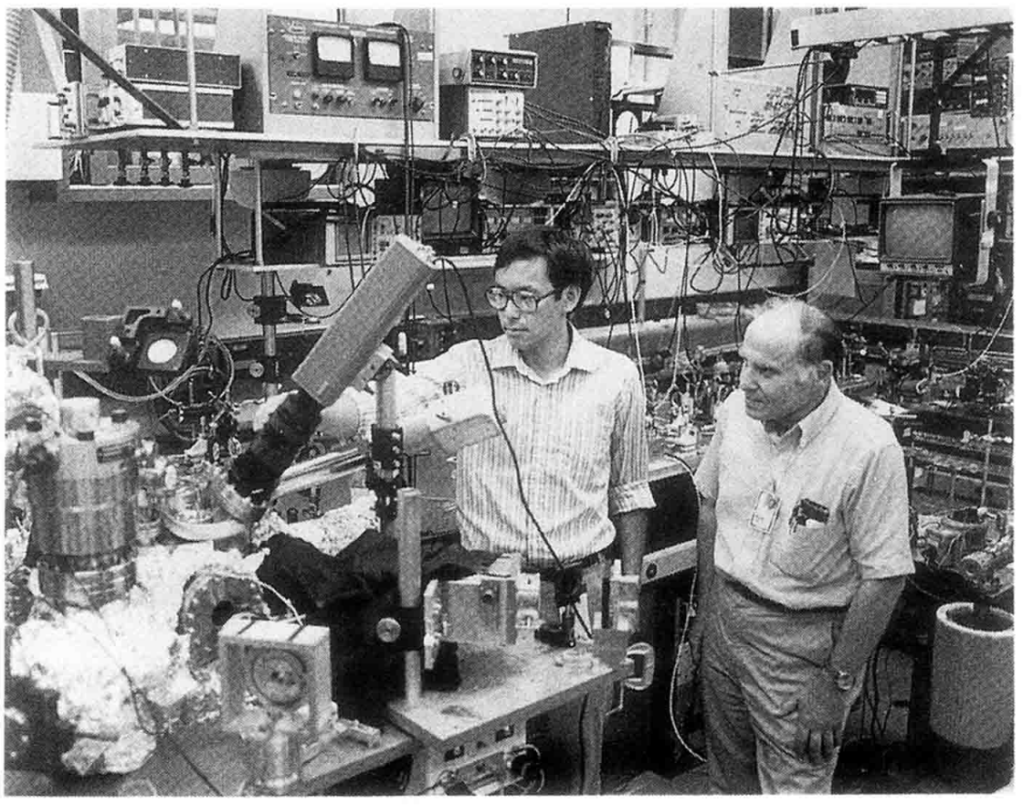

Aparna Deshpande is an Associate Professor of Physics at IISER Pune, specializing in atomic-scale exploration of two-dimensional materials and their interfaces using scanning tunneling microscopy. She is deeply engaged in research on nanomaterials and is active in physics education (as part of the department of science education at IISER Pune), communication, and outreach at IISER Pune.

Aparna is also the faculty in charge of the Smt. Indrani Balan Science Activity Centre at IISER Pune, where she leads diverse science outreach and STEM education initiatives, promoting hands-on multi-lingual learning and innovative workshops for students and teachers across India.

In this conversation, we explore her research in physics and science education.

You can also watch or listen on spotify

References:

[1] “Dr. Aparna Deshpande.” Accessed: Sept. 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://draparnadeshpande.github.io/portfolio/

[2] “Dr. Aparna Deshpande (@DrAparnaIISERP) / X.” X (formerly Twitter). Accessed: Sept. 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://x.com/draparnaiiserp

[3] “Aparna Deshpande | LinkedIn.” Accessed: Sept. 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.linkedin.com/in/aparna-deshpande-01927015/?originalSubdomain=in

[4] “Aparna Ramchandra Deshpande – Google Scholar.” Accessed: Sept. 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=f5FnqMIAAAAJ&hl=en

[5] “Aparna Deshpande – IISER Pune.” Accessed: Sept. 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.iiserpune.ac.in/research/department/physics/people/faculty/regular-faculty/aparna-deshpande/259

[6] J. Poskett, Horizons. London, UK: Penguin Books, 2023. Accessed: Sept. 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/313423/horizons-by-poskett-james/9780241986264

[7] P. Lockhart and K. Devlin, A Mathematician’s Lament. Illustrated ed. New York, NY: Bellevue Literary Press, 2009. https://www.blpress.org/books/a-mathematicians-lament/