Today, I complete 15 years as a faculty member at IISER-Pune. I have attempted to put together a list of some lessons (based on my previous writings) that I have learnt so far. A disclaimer to note is that this list is by no means a comprehensive one, but a text of self-reflection from my viewpoint on Indian academia. Of course, I write this in my personal capacity. So here it is..

- People First, Infrastructure Next

As an experimental physicist, people and infrastructure in the workplace are of paramount importance. When I am forced to prioritize between them, I have chosen people over infrastructure. I am extremely fortunate to have worked with, and continue to work with, excellent students, faculty colleagues, and administrative staff members. A good workplace is mainly defined by the people who occupy it. I do not neglect the role of infrastructure in academia, especially in a country like India, but people have a greater impact on academic life. - Create Internal Standards

In academia, there will always be evaluations and judgments on research, teaching, and beyond. Every academic ecosystem has its own standards, but they are generalized and not tailored to individuals. It was important for me to define what good work meant for myself. As long as internal standards are high and consistently met, external evaluation becomes secondary. This mindset frees the mind and allows for growth, without unnecessary comparisons. - Compare with Yourself, Not Others

The biggest stress in academic life often arises from comparison with peers. I’ve found peace and motivation in comparing my past with my present. Set internal benchmarks. Be skeptical of external metrics. Strive for a positive difference over time. - Constancy and Moderation

Intellectual work thrives not on intensity alone, but on constancy. Most research outcomes evolve over months and years. Constant effort with moderation keeps motivation high and the work enjoyable. Binge-working is tempting, but rarely effective for sustained intellectual output. - Long-Term Work

We often overestimate what we can do in a day or a week, and underestimate what we can do in a year. Sustained thought and work over time can build intellectual and technical monuments. Constancy is underrated. - Self-Mentoring

Much of the academic advice available is tailored for Western systems. Some of it is transferable to Indian contexts, but much of it is not. In such situations, I find it useful to mentor myself by learning from the lives and work of people who have done extraordinary science in India. I have been deeply inspired by many people, including M. Visvesvaraya, Ashoke Sen, R. Srinivasan, and Gagandeep Kang. - Write Regularly—Writing Is Thinking

Writing is a tool to think. Not just formal academic writing, but any articulation of thought, journals, blogs, drafts, clarifies and sharpens the mind. Many of my ideas have taken shape only after I started writing about them. Writing is part of the research process, not just a means of communicating its outcomes. - Publication is an outcome, not a goal Publication is just one outcome of doing research. The act of doing the work itself is very important. It’s where the real intellectual engagement happens. Focus on the process, not just the destination.

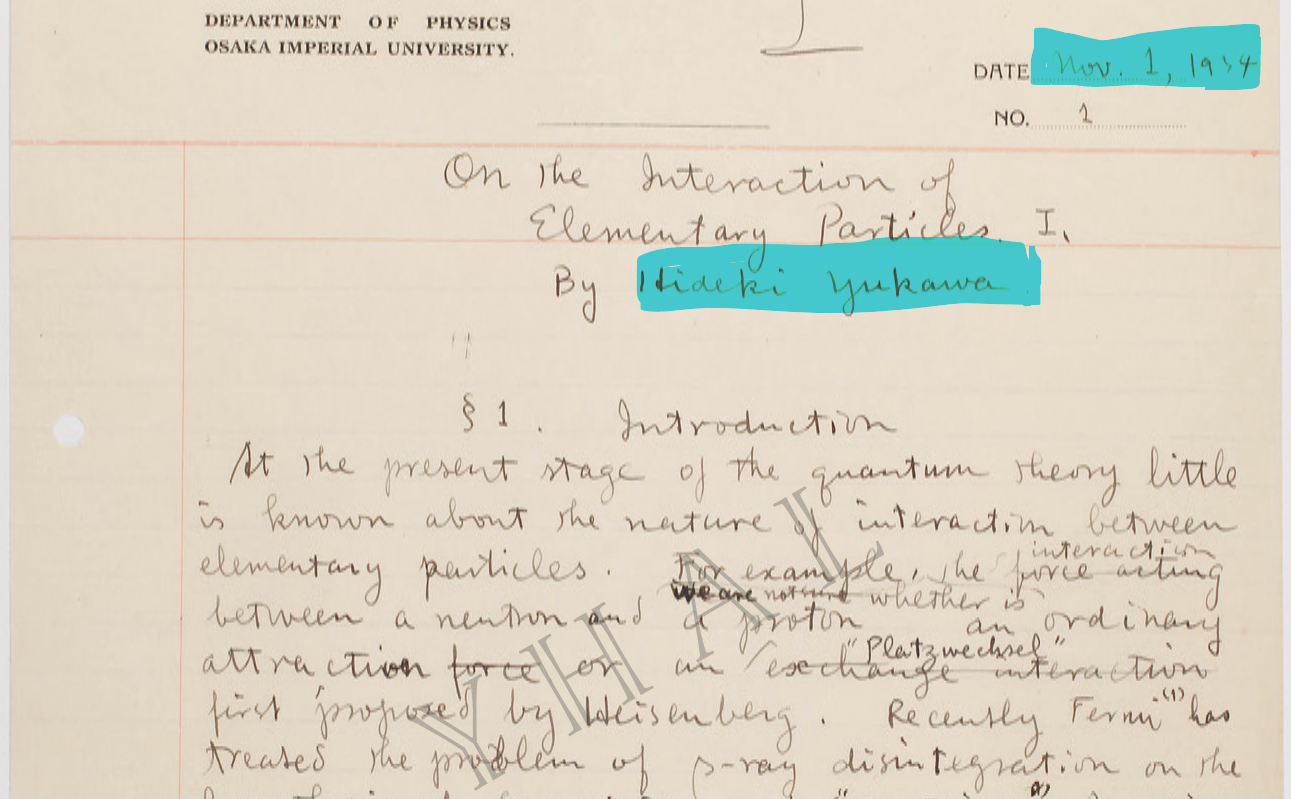

- Importance of History and Philosophy of Physics

Ever since my undergraduate days, I have been interested in the history and philosophy of science, especially physics. Although I never took a formal course, over time I have developed a deep appreciation for how historical and philosophical perspectives shape scientific understanding. They have helped me answer the fundamental question, “Why do I do what I do?” Reflecting on the evolution of ideas in physics—how they emerged, changed, and endured—has profoundly influenced both my teaching and research. - Value of Curiosity-Driven Side Projects

Some of the most fulfilling work I’ve done has emerged from side projects, not directly tied to funding deadlines or publication pressure, but driven by sheer curiosity. These projects, often small and exploratory, have helped me learn new tools, ask new questions, and sometimes even open up new directions in research. Curiosity, when protected from utilitarian pressures, can be deeply transformative. - Professor as a Post-doc

A strategy I found useful is to treat myself as a post-doc in my own lab. In India, retaining long-term post-docs is difficult. Hence, many hands-on skills and subtle knowledge are hard to transfer. During the lockdown, I was the only person in the lab for six months, doing experiments, rebuilding setups, and regaining technical depth. That experience was invaluable. - Teaching as a Social Responsibility

Scientific social responsibility is a buzzword, but for me, it finds its most meaningful expression in teaching. The impact of good teaching is often immeasurable and long-term. Watching students grow is among the most rewarding experiences in academia. Local, visible change matters. - Teaching Informally Matters

Teaching need not always be formal. Informal teaching, through conversations, mentoring, and public outreach, can be more effective and memorable. It is free of rigid expectations and evaluations. If possible, teach. And teach with joy. As Feynman showed us, it is a great way to learn. - Foster Open Criticism

In my group, anyone is free to critique my ideas, with reason. This open culture has been liberating and has helped me learn. It builds mutual respect and a more democratic intellectual space. - Share Your Knowledge

If possible, teach. Sharing knowledge is a fundamental part of academic life and enriches both the teacher and the learner. The joy of passing on what you know is priceless. - Social Media: Effective If Used Properly

Social media, if used responsibly, is a powerful tool, especially in India. It can bridge linguistic and geographical divides, connect scientists across the world, and communicate science to diverse audiences. For Indian scientists, it is a vital instrument of outreach and dialogue. My motivation to start the podcast was in this dialogue and self-reflection. - Emphasis on Mental and Physical Health

In my group, our foundational principle is clear: good health first, good work next. Mental and physical well-being are not optional; they are necessary conditions for a sustainable, meaningful academic life. There is no glory in research achieved at the cost of one’s health. - Science, Sports, and Arts: A Trinity

I enjoy outdoor sports like running, swimming, and cricket. Equally, I love music, poetry, and art from all cultures. This trinity of pursuits—science, sports, and the arts—makes us better human beings and enriches our intellectual and emotional lives. They complement and nourish each other. - Build Compassion into Science

None of this matters if the journey doesn’t make you a better human being. Be kind to students, collaborators, peers, and especially yourself. Scientific research, when done well, elevates both the individual and the collective. It has motivated me to humanize science. - Academia Can Feed the Stomach, Brain, and Heart

Academia, in its best form, can feed your stomach, brain and heart. Nurturing and enabling all three is the overarching goal of academics. And perhaps the goal of humanity.

My academic journey so far has given me plenty of reasons to love physics, India and humanity. Hopefully, it has made me a better human being.