A bit of random thinking on critical thinking..a slide show..

Category: science

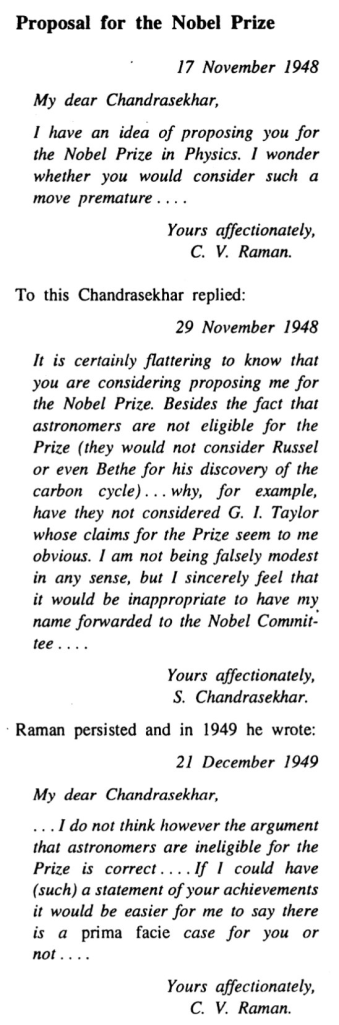

Raman-Chandra Letters

Horizons – book reco

link to the book on Amazon

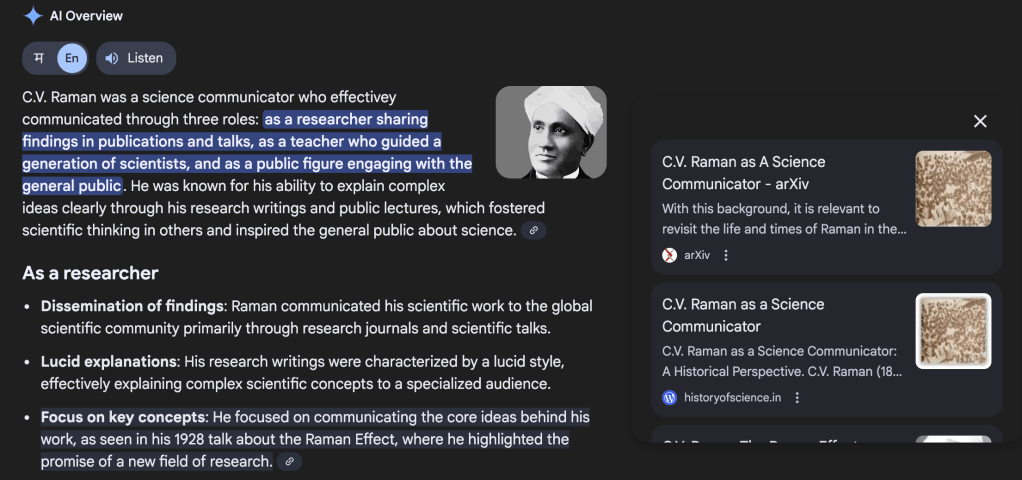

Raman essay and Open-Access

I see that the essay I wrote on CV Raman and made open access (thanks to Resonance, which published it) has been used by several educators on YouTube, including some in Indian languages. Also, the Google AI overview shows the published essay as the main reference for a search related to Raman’s science communication (see slideshow below).

I am glad to see that making one’s writing open to all has positive effects. Open-access, not just for readers, but also for authors, is beneficial. Especially in India, paywalls for science are a detriment.

My worry is that open-access publishing has been mainly driven by commercial publishers that extract huge funds from the publishing authors. This defeats the purpose of open science, especially when the research of an author is publicly funded. Added to that, Indian researchers and writers cannot afford to pay huge sums for publishing articles and books.

The publication landscape (including journals and books) across the world needs an introspection. Open-access model is effective only when the readers and authors have access to that model. Otherwise, the model becomes a paywall for authors.

Opinion on maths

From my Substack conversation

Humanizing Science – A Conversation with a Student

Recently, I was talking to a college student who had read some of my blogs. He was interested in knowing what it means to humanize science. I told him that there are at least three aspects to it.

First is to bring out the wonder and curiosity in a human being in the pursuit of science. The second was to emphasize human qualities such as compassion, effort, mistakes, wrong directions, greed, competition and humour in the pursuit of science. The third thing was to bring out the utilitarian perspective.

The student was able to understand the first two points but wondered why utility was important in the pursuit of humanizing science. I mentioned that the origins of curiosity and various human tendencies can also be intertwined with the ability to use ideas. Some of the great discoveries and inventions, including those in the so-called “pure science” categories, have happened in the process of addressing a question that had its origin in some form of an application.

Some of the remarkable ideas in science have emerged in the process of applying another idea. Two great examples came into my mind: the invention of LASERs, and pasteurization.

I mentioned that economics has had a major role in influencing human ideas – directly or indirectly. As we conversed, I told the student that there is sometimes a tendency among young people who are motivated to do science to look down upon ideas that may have application and utility. I said that this needs a change in the mindset, and one way to do so is to study the history, philosophy and economics of science. I said that there are umpteen examples in history where applications have led to great ideas, both experimental and theoretical in nature, including mathematics.

Further, the student asked me for a few references, and I suggested a few sources. Specifically, I quoted to him what Einstein had said:

“….So many people today—and even professional scientists—seem to me like someone who has seen thousands of trees but has never seen a forest. A knowledge of the historic and philosophical background gives that kind of independence from prejudices of his generation from which most scientists are suffering. This independence created by philosophical insight is—in my opinion—the mark of distinction between a mere artisan or specialist and a real seeker after truth..”

The student was pleasantly surprised and asked me how this is connected to economics. I mentioned that physicists like Marie Curie, Einstein and Feynman did think of applications and referred to the famous lecture by Feynman titled “There is Plenty of Room at the Bottom” (1959).

To give a gist of his thinking, I showed what Feynman had to say on miniaturization:

“There may even be an economic point to this business of making things very small. Let me remind you of some of the problems of computing machines. In computers we have to store an enormous amount of information. The kind of writing that I was mentioning before, in which I had everything down as a distribution of metal, is permanent. Much more interesting to a computer is a way of writing, erasing, and writing something else. (This is usually because we don’t want to waste the material on which we have just written. Yet if we could write it in a very small space, it wouldn’t make any difference; it could just be thrown away after it was read. It doesn’t cost very much for the material).”

I mentioned that this line of thinking on minaturization is now a major area of physics and has reached the quantum limit. The student was excited and left after noting the references.

On reflecting on the conversation, now I think that there is plenty of room to humanize science.

Why is astronomy interesting? Chandra likes Wigner’s answer

The questions “Why is astronomy interesting; and what is the case for astronomy?” have intrigued me; I have often discussed these questions with my friends and associates. Granted that physical science, as a whole, is worth pursuing, the question is what the particular case for astronomy is? My own answer has been this: Physical science deals with the entire range of natural phenomena; and nature exhibits different patterns at different levels; and the patterns of the largest scales are those of astronomy. (Thus Jeans’ criterion of gravitational instability is something which we cannot experience except when the scale is astronomical.) Of the many other answers to my questions, I find the following of Wigner most profound: “The study of laboratory physics can only tell us what the basic laws of nature are; only astronomy can tell us what the initial conditions for those laws are.”

from A Scientific Autobiography: S. Chandrasekhar (2011) by edited by Kameshwar C. Wali

‘We’gnana !

Recently, I saw the following tweet from the well-known historian William Dalrymple.

Congrats to the listed authors, who deserve rewards (and the money) for their effort.

I have 3 adjacent points to make:

1) India badly needs to read (and write) more on science and technology. Here, I am not referring to textbooks, but some popular-level science books (at least). Generally, educated Indians are exposed to science only through their textbooks, which are mostly dull, or, in this era, YouTube videos, which have a low signal-to-noise ratio. Good quality science & tech books at a popular level can add intellectual value, excitement, and expand scientific thinking via reading, not just in students, but also in adults.

2) In India, most of the non-fiction literature is dominated by the social sciences, particularly history (as seen in the best-seller list). I have no problem with that, but non-fiction as a genre is a broad tree. Indian readers (and publishers) can and should broaden this scope and explore other branches of the tree. Modern science books (authentic ones), especially written in the Indian context, are badly in need. I hope trade publishers are reading this!

3) Most of the public and social media discourse in India does not emphasize (or underplays) the scientific viewpoint. Scientific literature and scientific discourse should become a central part of our culture. Good books have a major role to play. Remember what Sagan’s Cosmos did to American scientific outlook, and indirectly to its economic progress. The recent Nobel in economics, especially through the work of Joel Mokyr, further reinforces the connection between science, economics and human progress. This realization should be bottom-up, down to individual families and public places.

One of the great scientists, James Maxwell, is attributed to have said: “Happy is the man who can recognise in the work of today a connected portion of the work of life and an embodiment of the work of Eternity.…“

Science, with its rich, global history and philosophy, in the form of good books, can connect India (and the world) to the ‘work of eternity’, and make us look forward.

Embedding science within culture, in a humane way, can lead to progress. Science books have a central role to play in this.

विज्ञान (Vignana) should transform to ‘We’gnana !

Ability to Wonder

More than 25 years ago, Prof. G. Srinivasan (RRI, Bengaluru), in an astrophysics class, narrated something that has stuck in my mind.

I am paraphrasing here.

He told us about a conversation he had with Prof. Jocelyn Bell, the discoverer of pulsars (rotating neutron stars).

When Jocelyn was asked: What is the most important quality to do scientific research?

She replied: ‘ability to wonder’.

Some writing advice (mainly physics) for UG students

Some writing advice (mainly physics) I shared with my undergraduate class. This may be useful to others.

- Equations, data and figures make meaning when you include a context. This context is expressed using words. Symbols and data by themselves cannot complete the meaning of an argument, unless one knows the context. A common mistake undergraduates make in an exam is to answer questions using only symbols and figures and assume the reader can understand the context.

- One way to treat writing in physics (in this case, an exam paper or an assignment) is to imagine you are talking to a fellow physics student who is not part of the course you are writing about. This means you can assume some knowledge, but not the context. Anticipate their questions and address them in the text you are writing. This model also works while writing research papers with some caveats.

- While you refer to equations, data and figures in your assignment, make sure you cite the reference at the location of the content you are discussing. Merely listing the references at the end of the document does not make the connection. Remember, while talking, you never do this kind of referencing.

- It is useful to structure your arguments with headings, sub-headings and a numbered list. This gives a visual representation of your arguments. You may not find this kind of structured writing in novels, other forms of fictional writing and also in some literature related to social sciences, but in natural sciences with dense information, this will be very useful. Always remember, while writing science (or any form of nonfiction writing), clarity comes before aesthetics.

Also, below is another blog related to written assignments.