Let me draw attention, especially of those interested in scientific research, to a relevant review article in Nature Reviews Physics titled “On scientific understanding with artificial intelligence“

Below are a couple of paragraphs that caught my attention:

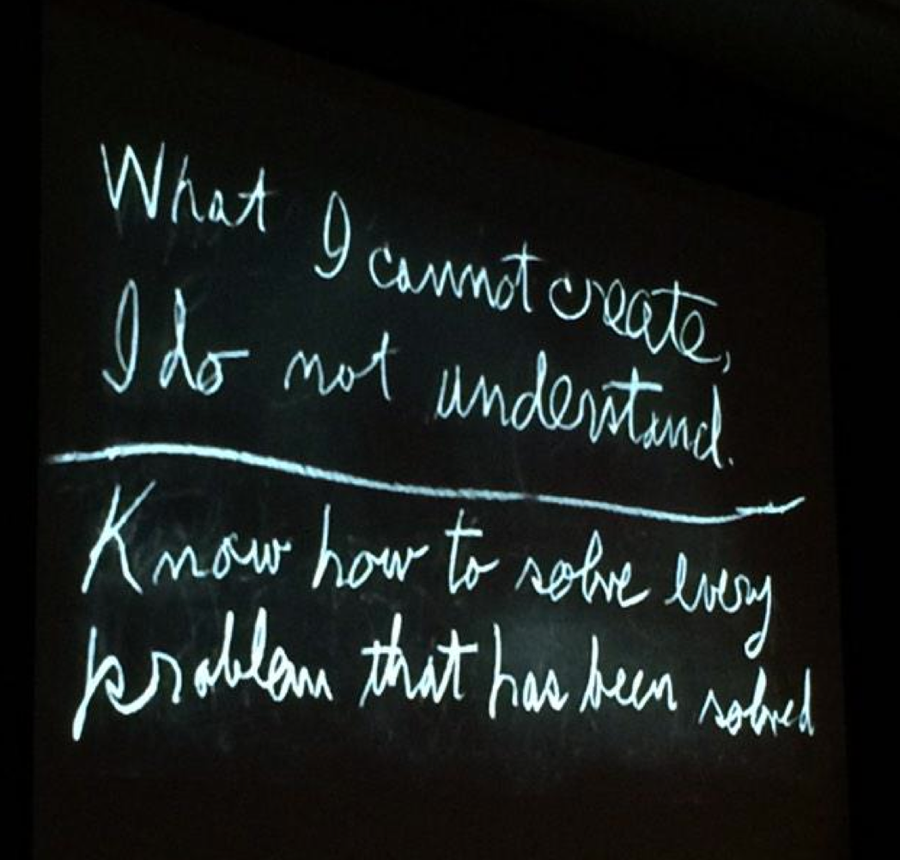

“Scientific understanding and scientific discovery are both important aims in science. The two are distinct in the sense that scientific discovery is possible without new scientific understanding….

…..to design new efficient molecules for organic laser diodes, a search space of 1.6 million was explored using ML and quantum chemistry insights. The top candidate was experimentally synthesized and investigated. Thereby, the authors of this study discovered new molecules with very high quantum efficiency. Whereas these discoveries could have important technological consequences, the results do not provide new scientific understanding.”

The authors provide two more examples of a similar kind, from different branches of science.

The authors conclude:

“Undoubtedly, advanced computational methods in general and in AI specifically will further revolutionize how scientists investigate the secrets of our world. We outline how these new methods can directly contribute to acquiring new scientific understanding. We suspect that significant future progress in the use of AI to acquire scientific understanding will require multidisciplinary collaborations between natural scientists, computer scientists and philosophers of science. Thus, we firmly believe that these research efforts can — within our lifetimes — transform AI into true agents of understanding that will directly contribute to one of the main goals of science, namely, scientific understanding.”

Worth reading the full article. Link here.

PS: Prof. Siddharth Tallur (IIT, Bombay) on LinkedIn raised an important question.

Nice.. thanks for sharing, will go through it. Although a lot of brute force seems to be passed off as understanding these days (brawn = brain?) I wonder if AI and ML of the varieties we have today are advancements in computing or intelligence?

My reply:

The computational capability is undoubtedly great, and probably the coding/software domain has been conquered, but there is a tendency to extrapolate the immediate impact of AI to every domain of human life, where even basic tech has not made an impact. That needs deeper knowledge of interfacing AI with other domains of engineering.

Embedding AI in the virtual domain is one thing, but to put it in the real world with noise is a different game altogether. That needs interfacing with the physical world, and there is also an energy expense that doesn’t get factored into the discussion. It has great potential, and I’m eager to see its impact on the physical infrastructure. Parallelly, it is interesting to see how it has been sold in the public domain.

made a video to explain the main blog: