Meghnad Saha (6 October 1893 – 16 February 1956), of the fame of Saha’s ionization formula, was born this day. In 1993, a postage stamp in India was released commemorating his birth centenary.

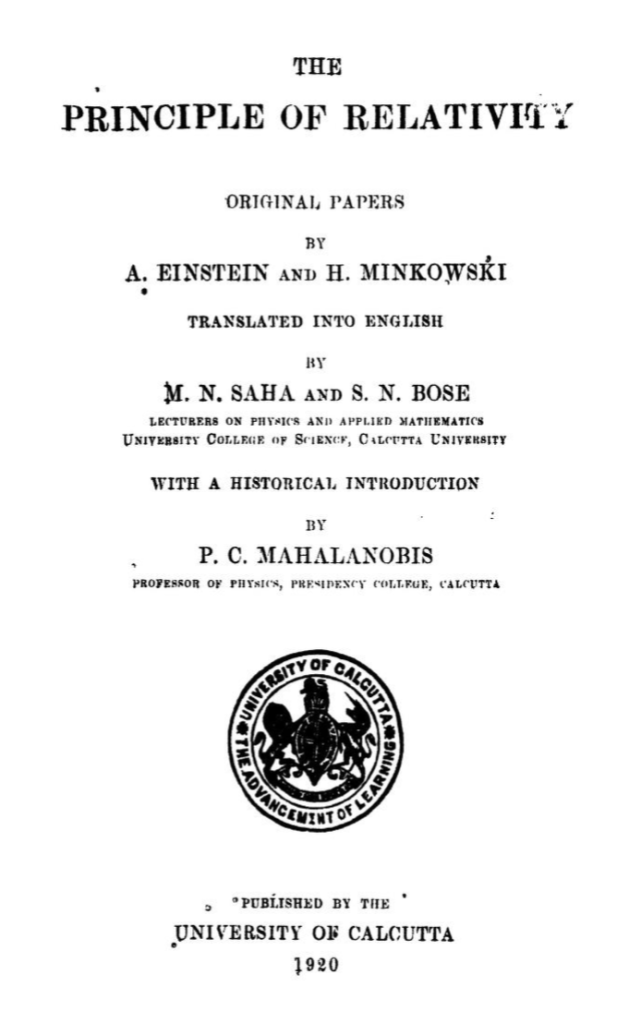

Saha was an astrophysicist with a broad knowledge and appreciation of various branches of physics. One of the earliest English translations (1920) of the papers on relativity by Einstein and Minkowski was written by Meghnad Saha and S.N.Bose.

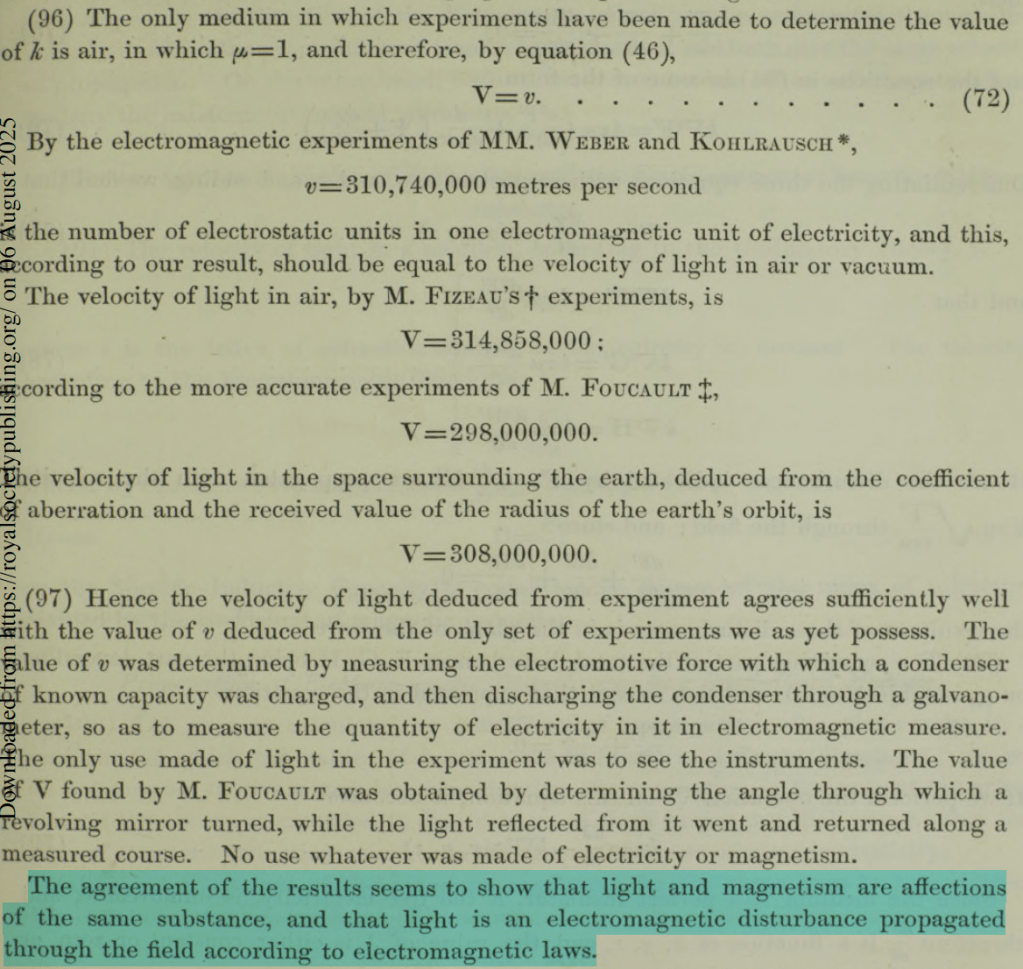

At the beginning of the book, Mahalanobis introduces the topic with a historical introduction. He begins with a thoughtful discussion on experiments that eventually ruled out the presence of ether, and it sets the stage as follows:

“Lord Kelvin writing in 1893 in hig preface to the English edition of Hertz’s Researches on Electric Waves, says many workers and many thinkers have helped to build up the nineteenth century school of plenum, one ether for light, heat, electricity, magnetism; and the German and English volumes containing Hertz’s electrical papers, given to the world in the last decade of the century, will be a permanent monument of the splendid consummation now realised.”

Ten years later, in 1905, we find Einstein declaring that “the ether will be proved to be superflous”. At first sight the revolution in scientific thought brought about in the course of a single decade appears to be almost too violent. A more careful even though a rapid review of the subject will, however, show how the Theory of Relativity gradually became a historical necessity.

Towards the beginning of the nineteenth century, the luminiferous ether came into prominence as a result of the brilliant successes of the wave theory in the hands of Young and Fresnel. In its stationary aspect, the elastic solid ether was the outcome of the search for a medium in which the light waves may “undulate.” This stationary ether, as shown by Young, also afforded a satisfactory explanation of astronomical aberration. But its very success gave rise to a host of new questions all bearing on the central problem of relative motion of ether and matter.“

Saha, in various capacities, took a stance against British colonialism. Although it affected some opportunities, he continued to do science and was recognized for his outstanding contributions. As Rajesh Kochhar mentions:

“Saha had wanted to join the government service, but was refused permission because of his pronounced anti-British stance. For the same reason, the British government would have liked The Royal Society to exclude Saha. It goes to the credit of the Society that it ignored the pressures and the hints, and elected him a fellow, in 1927. This recognition brought him an annual research grant of £300 from the Indian government followed by the Royal Society’s grant of £250 in 1929 (DeVorkin 1994, p. 164).“

Saha led a tough life. He not only had to face suppressive British colonial rule but also academic politics and battles (versus Raman, no less). His knowledge of physics, his contributions to Indian science, and his commitment to people (he was a politician too) were significant. Let me end the blog with a few lines from Arnab Rai Choudhuri’s article, which nicely summarizes Saha’s work (specifically his ionization formula), and his scientific life:

“Saha’s tale of extraordinary scientific achievements is simultaneously a tale of triumph and defeat, a tale both uplifting and tragic. Saha showed what a man coming from a humble background in an impoverished colony far from the active centres of science could achieve by the sheer intellectual power of his mind. But his inability to follow the trail which he himself had blazed makes it clear that there are limits to what even an exceptionally brilliant person could achieve in science under very adverse circumstances.“

India and Indian science should remember Meghnad Saha.