Jan 2026 – Apr 2026 – I am teaching a course on Quantum Optics. Below you will find some random thoughts and notes related to my reading. I will be updating the list as I go along the semester. You can add your comments below.

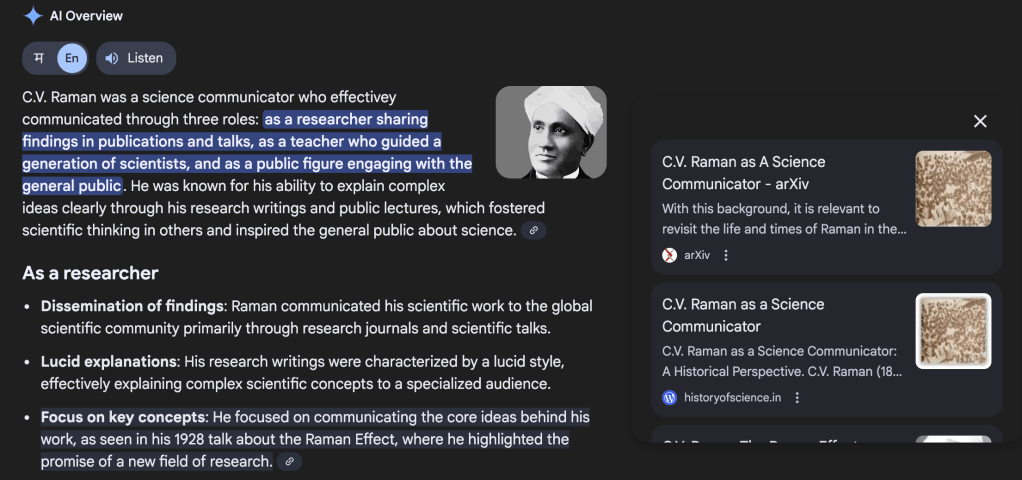

- Anyone interested in physics should know a bit about renormalized QED and the efforts that went behind it… It still remains a benchmark of how experiments and theory work in elevating each other…

- Hari Dass (erstwhile, IMSc) on FB made an interesting observation:it’s unfortunate that after all those and subsequent developments, a mystery is being built out of renormalisation..it was the price to pay for assuming, without any justification, that the microscopic description held to arbitrarily small distances..wilson,schwinger and even feynman have clarified that the right way to do physics is to start with an effective description with a cutoff, which can be fully quantum in nature, and keep extending it to higher and higher scales with the help of further data, as well as with better theoretical understanding..

- “The photon is the only particle that was known as a field before it was detected as a particle.”

- This is how Weinberg introduces the birth of quantum field theory. He further adds: “Thus it is natural that the formalism of quantum field theory should have been developed in the first instance in connection with radiation and only later applied to other particles and fields.”Ref: S. Weinberg (in Quantum Theory of Fields, p.15, 1995)

- Sudipta Sarkar (IIT G) made an interesting observation in facebook:

- “In some sense, it did right! Dirac started QFT with the effort to quantise radiation! But formally, it is not easy to write down the quantum version of electrodynamics owing to gauge symmetry. It took quite a bit of time to understand how to manage a quantum theory with massless states!“

- My reply: “indeed..the reconciliation of symmetry was a bottleneck. I am also amazed by the progress of thought, especially by Dirac, who took the harmonic oscillator problem and treated it the way he did. Historically, the question of quantization of particles was already an established programme, but to quantize the field was indeed a major challenge, and hence ‘second quantization’.“

- The concept of creation and annihilation operators is an intriguing one because it brings in the thoughts from the commutation relationship that existed in classical physics and transfers that into quantum mechanics. This intellectual connection is mainly attributed to Dirac, and historically, this has been one of the most important connections to be made. The question of field quantization already existed in 1920s, but it is thanks to Dirac who really made this connection in a systematic and mathematically consistent way.

- Sudipta Sarkar (IIT G) made an interesting observation in facebook:

- This is how Weinberg introduces the birth of quantum field theory. He further adds: “Thus it is natural that the formalism of quantum field theory should have been developed in the first instance in connection with radiation and only later applied to other particles and fields.”Ref: S. Weinberg (in Quantum Theory of Fields, p.15, 1995)

- In the context of the quantum harmonic oscillator model of electromagnetic radiation, the shift from canonical variables such as position and momentum to creation and annihilation operators is a fascinating one. Interestingly, this progression further leads to the so-called number operator. It is also a progression from Hermitian to non-Hermitian and again back to a Hermitian operator. In the process of understanding the number operators, one realizes that the ground-state results in the so-called zero-point energy. Taken further, the commutation of the number operator with the electric field of the electromagnetic radiation results in the number-amplitude uncertainty. This further gives an insight into why the field amplitude has a non-zero spread, even for the n = 0 state, and therefore results in the so-called vacuum fluctuations.

- It can’t get more quantum than this…

- An essay on Quantum States in Argand Diagrams: https://historyofscience.in/2026/02/03/quantum-states-in-argand-diagrams-vacuum-coherent-and-squeezed/