In the late 1920s, the quantum theory of matter was still under construction. Questions such as what are the constituents of a nucleus of an atom were pertinent. The then understanding was that a nucleus was made of protons and electrons. Yes, you read it right. People thought that electrons were part of an atomic nucleus. But those were the times when quantum theory was evolving, and many ‘uncertainties’ persisted. For example, if one considered a nitrogen nuclei, it was postulated that it had 14 protons and 7 electrons.

The other important aspect during that time was the question of spin statistics, including that of nuclei, which was under exploration. The classification of nuclear spin in terms of Fermi-Dirac statistics or Bose-Einstein statistics was under study, and researchers were trying to sort it from theoretical and experimental viewpoints. Going back to the example of nitrogen nuclei, it was categorized to obey Fermi-Dirac statistics.

Enter Rasetti and his Raman Spectra

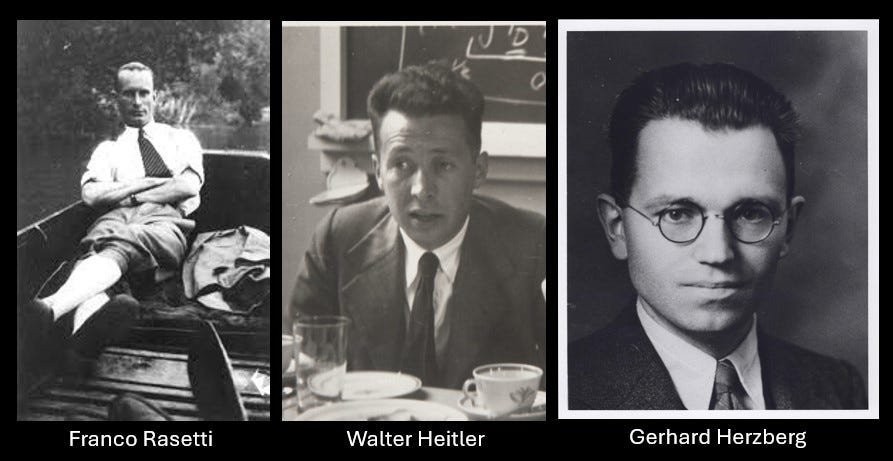

With this backdrop, let me introduce you to Franco Rasetti. Franco was an Italian physicist who was visiting Caltech in the US on a research fellowship. This was 1929, and many exciting quantum thoughts were in the air. C. V. Raman had just discovered an inelastic scattering process in the visible frequency spectra of molecules, and there was interest in understanding the quantum nature of the interaction between light and matter. Motivated by this, Rasetti set up an experiment at Caltech to probe Raman spectral features of molecular gases. Rasetti was an elegant experimentalist and, later, went on to become a close associate of Enrico Fermi and played a crucial role in the nuclear fission experiment[I].

Coming back to the work of Rasetti’s experiment, he took up the problem of understanding the Raman effect in diatomic gases (nitrogen and oxygen) and wrote a series of papers[ii]. Among them, he published his observations on rotational Raman spectra of diatomic gases (nitrogen and oxygen). Specifically, he performed a series of experiments and recorded beautiful spectral features of rotational lines of diatomic nitrogen. In that work, Rasetti discussed the specific selection rules from an experimentalist viewpoint and identified that the even lines in the spectral features were much more intense compared to the odd lines.

Guys from Gottingen

During the same year, working in Göttingen as postdocs of Max Born were Walter Heitler and Gerhard Herzberg. These two gentlemen studied the paper of Rasetti with great interest and went on to write an interesting paper in Naturwissenschaften (in German)[iii]. The translated title of the paper was “Do Nitrogen Nuclei Obey Bose Statistics”.

In that paper, Heitler and Herzberg studied rotational Raman features of nitrogen molecules and compared them to hydrogen molecules. They considered arguments based on the symmetry of the eigenfunctions and associated them with statistics (Fermi or Bose). Hydrogen nuclei obeyed Fermi-Dirac statistics, whereas Nitrogen counterpart did not. From the analysis of symmetry, they found that Rasetti’s observation contradicted the convention that Nitrogen nuclei obey Fermi-Dirac statistics. So, with this contrast, they clearly indicated that the nuclei of nitrogen should obey Bose-Einstein statistics, provided Rasetti’s experiments were correct.

How was the discrepancy resolved?

In 1932, James Chadwick[iv] went on to discover the neutron, and this discovery laid the foundation for understanding the constituent of a nucleus. With the new observation, one had to account for the presence of neutrons inside the nucleus. In the context of Nitrogen nuclei, it was found that it contained 7 protons and 7 neutrons, and the total spin was 1 (in contrast to spin ½ of hydrogen). This ascertained that Nitrogen nuclei obeyed Bose-Einstein statistics and removed the discrepancy from the observed rotational Raman spectra of Rasetti.

3 takeaways

What can we learn from this story? The first aspect is that experiments and theory go hand in hand in physics. They positively add value to each other and connect the real to the abstract thought. Second, it emphasizes the importance of careful observations and their interpretation. The third lesson is that Rasetti, Heitler and Herzberg were all young people and learned from each other’s work. They were essentially post-docs when they did this work, and we are still discussing it today.

Sometimes, good work has a long life.

[i] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franco_Rasetti

[ii] https://www.nature.com/articles/123205a0

https://www.pnas.org/doi/epdf/10.1073/pnas.15.3.234

https://www.pnas.org/doi/epdf/10.1073/pnas.15.6.515

[iii] https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF01506505

[iv] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Chadwick