Today is India’s National Science Day. It celebrates the discovery of Raman effect on 28th February, 1928.

For more details on the discovery of the effect, and various human aspects related to it : you can see my past blogs here, here, here and here.

In this blog, I will briefly discuss about some of the work that directly influenced Raman’s thinking that further led to a remarkable discovery that we know by his name.

All creative pursuits are motivated by ideas from the past. No one gets their ideas in vacuum. All of us are influenced by the information which we perceive and receive. This means consciously or subconsciously the world that we are creating, both in our minds and in reality, is fundamentally influenced by the information in the world.

The discovery behind the Raman effect is no exception to this particular principle. In his formative years, C V Raman was heavily influenced by the research of Rayleigh and Helmholtz, and some classical thinkers including Euclid. Raman was also closely following the development of quantum mechanics in the early 1920s, and he was keenly studying the theoretical and experimental developments in this field.

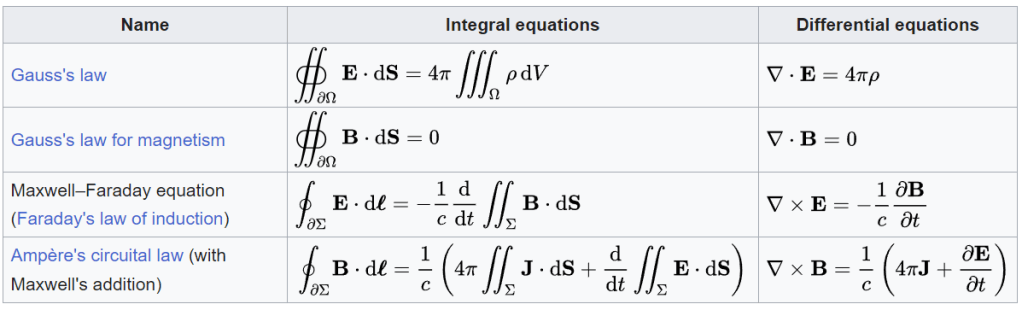

Two aspects which played a crucial role in motivating Raman’s (Nobel prize winning) work was Compton scattering and Kramers-Heisenberg formula.

Compton scattering was as outstanding experimental achievement that revealed two aspects of light-matter interaction. First, it demonstrated inelastic scattering of electromagnetic radiation interacting with a quantum object (in this case free electrons) in the laboratory frame. Second is that it laid a foundation to revisit the wave-particle duality of light from an experimental viewpoint. Raman and Krishnan’s main paper on light scattering starts by explicitly referring to Compton effect, and motivates observation for optical analogue of Compton scattering.

To quote from Raman’s Nobel lecture :

“In interpreting the observed phenomena, the analogy with the Compton effect was adopted as the guiding principle. The work of Compton had gained general acceptance for the idea that the scattering of radiation is a unitary process in which the conservation principles hold good.”

Next is the Kramers-Heisenberg formula. This mathematical description gives the scattering cross section of a photon interacting with a quantum object (in this case electron). This formula uses second-order perturbation theory, and evokes the famous ‘sum of all the intermediate states’ for non-resonant optical interaction. PAM Dirac played a vital role in deriving this formula from a quantum mechanical framework of radiation. An important and logical consequence of this formula is the emergence of stimulated emission of radiation, and this has had deep implications in understanding LASERs. Raman was keenly studying the formula and made a brilliant conceptual connection between laboratory observation and this formula that revealed the scattering cross-section.

Again to quote from Raman’s Nobel lecture:

“The work of Kramers and Heisenberg, and the newer developments in quantum mechanics which have their root in Bohr’s correspondence principle seem to offer a promising way of approach towards an understanding of the experimental results.”

The above two concepts were important ideas that motivated Raman scattering experiments. Importantly it highlights the jugalbandi between theoretical intuition with concrete experimental observations, which forms the bedrock of modern physics.

Newton famously mentioned about the discoveries he made by ‘standing on the shoulders of the giants’. Various people involved in creative pursuits including scientists acknowledge the fact that new ideas emerge from convergence/mutation of old ideas. The harder part of creativity in science, or for that matter any art form, is to choose the right ideas to combine so that the ’emergent’ new idea has greater value compared to the individual parts. In that sense, science is a great form of creative activity that not only combines old ideas to create new valuable ideas, but also transforms the perspective of the individual seed ideas. Thus ideas combine and evolve.

So let us combine good ideas and evolve. Happy Science Day !