Author: G.V. Pavan Kumar

Current Science – Editorial Board

I have joined the editorial board of Current Science (Indian Academy of Sciences)

Look forward to papers on the listed topics in the physical science section.

Hints Before a Discovery: The Case of Neutrons

In the late 1920s, the quantum theory of matter was still under construction. Questions such as what are the constituents of a nucleus of an atom were pertinent. The then understanding was that a nucleus was made of protons and electrons. Yes, you read it right. People thought that electrons were part of an atomic nucleus. But those were the times when quantum theory was evolving, and many ‘uncertainties’ persisted. For example, if one considered a nitrogen nuclei, it was postulated that it had 14 protons and 7 electrons.

The other important aspect during that time was the question of spin statistics, including that of nuclei, which was under exploration. The classification of nuclear spin in terms of Fermi-Dirac statistics or Bose-Einstein statistics was under study, and researchers were trying to sort it from theoretical and experimental viewpoints. Going back to the example of nitrogen nuclei, it was categorized to obey Fermi-Dirac statistics.

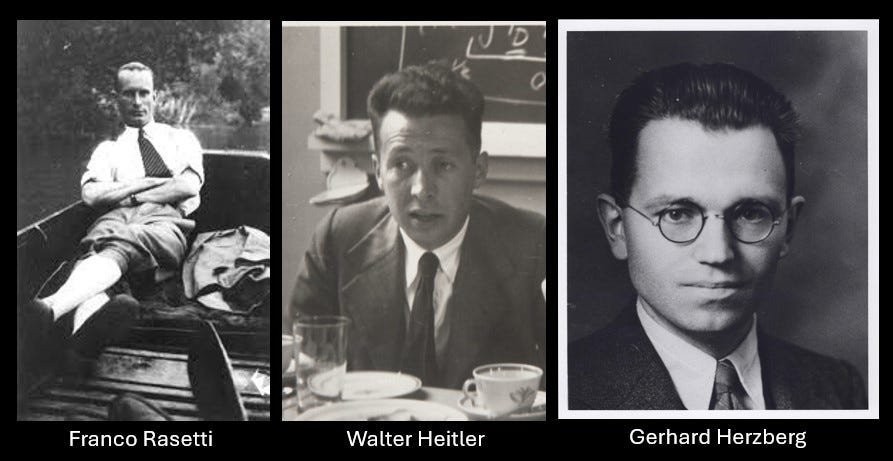

Enter Rasetti and his Raman Spectra

With this backdrop, let me introduce you to Franco Rasetti. Franco was an Italian physicist who was visiting Caltech in the US on a research fellowship. This was 1929, and many exciting quantum thoughts were in the air. C. V. Raman had just discovered an inelastic scattering process in the visible frequency spectra of molecules, and there was interest in understanding the quantum nature of the interaction between light and matter. Motivated by this, Rasetti set up an experiment at Caltech to probe Raman spectral features of molecular gases. Rasetti was an elegant experimentalist and, later, went on to become a close associate of Enrico Fermi and played a crucial role in the nuclear fission experiment[I].

Coming back to the work of Rasetti’s experiment, he took up the problem of understanding the Raman effect in diatomic gases (nitrogen and oxygen) and wrote a series of papers[ii]. Among them, he published his observations on rotational Raman spectra of diatomic gases (nitrogen and oxygen). Specifically, he performed a series of experiments and recorded beautiful spectral features of rotational lines of diatomic nitrogen. In that work, Rasetti discussed the specific selection rules from an experimentalist viewpoint and identified that the even lines in the spectral features were much more intense compared to the odd lines.

Guys from Gottingen

During the same year, working in Göttingen as postdocs of Max Born were Walter Heitler and Gerhard Herzberg. These two gentlemen studied the paper of Rasetti with great interest and went on to write an interesting paper in Naturwissenschaften (in German)[iii]. The translated title of the paper was “Do Nitrogen Nuclei Obey Bose Statistics”.

In that paper, Heitler and Herzberg studied rotational Raman features of nitrogen molecules and compared them to hydrogen molecules. They considered arguments based on the symmetry of the eigenfunctions and associated them with statistics (Fermi or Bose). Hydrogen nuclei obeyed Fermi-Dirac statistics, whereas Nitrogen counterpart did not. From the analysis of symmetry, they found that Rasetti’s observation contradicted the convention that Nitrogen nuclei obey Fermi-Dirac statistics. So, with this contrast, they clearly indicated that the nuclei of nitrogen should obey Bose-Einstein statistics, provided Rasetti’s experiments were correct.

How was the discrepancy resolved?

In 1932, James Chadwick[iv] went on to discover the neutron, and this discovery laid the foundation for understanding the constituent of a nucleus. With the new observation, one had to account for the presence of neutrons inside the nucleus. In the context of Nitrogen nuclei, it was found that it contained 7 protons and 7 neutrons, and the total spin was 1 (in contrast to spin ½ of hydrogen). This ascertained that Nitrogen nuclei obeyed Bose-Einstein statistics and removed the discrepancy from the observed rotational Raman spectra of Rasetti.

3 takeaways

What can we learn from this story? The first aspect is that experiments and theory go hand in hand in physics. They positively add value to each other and connect the real to the abstract thought. Second, it emphasizes the importance of careful observations and their interpretation. The third lesson is that Rasetti, Heitler and Herzberg were all young people and learned from each other’s work. They were essentially post-docs when they did this work, and we are still discussing it today.

Sometimes, good work has a long life.

[i] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franco_Rasetti

[ii] https://www.nature.com/articles/123205a0

https://www.pnas.org/doi/epdf/10.1073/pnas.15.3.234

https://www.pnas.org/doi/epdf/10.1073/pnas.15.6.515

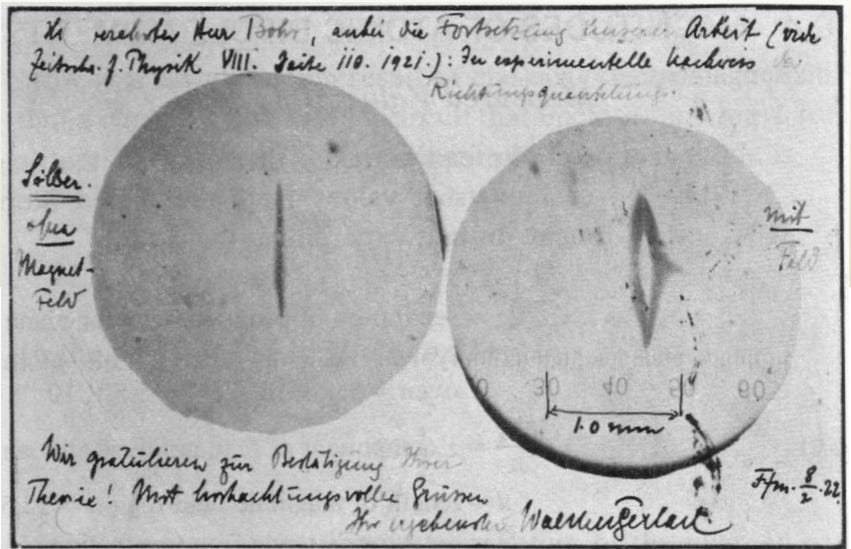

Stern-Gerlach experiment – the first picture

During the formative years of quantum mechanics (early 1900s), the spin and orbital angular momentum of atoms were found to be quantized by theoretical arguments. Experimental proof was lacking.

Stern-Gerlach experiment provided the first experimental proof in 1922. They took a beam of neutral silver atoms and deflected them through an inhomogeneous magnetic field.

Silver atoms have an unpaired electron in their outermost orbit. If they were to obey quantum mechanics, they should exhibit a spin of +1/2 or -1/2. When subjected to an external magnetic field, the electrons with +1/2 or -1/2 should spatially split into two. That is exactly what Stern and Gerlach observed, and below is the first picture of the same.

To quote the authors:

Gerlach’s postcard, dated 8 February 1922, to Niels Bohr. It shows a photograph of the beam splitting, with the message, in translation: “Attached [is] the experimental proof of directional quantization. We congratulate [you] on the confirmation of your theory.” (Courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives.)

This experiment was one of the most important observations in quantum mechanics and further confirmed the quantization of spins, which is now common knowledge in physics.

Superstitions – Kepler, Galileo & Newton

Superstition is a belief system or behavior of an individual that cannot be justified with evidence and logic. It is usually associated with people who do not (or do not want to) think critically. From the history and philosophy of science, we learn that a few famous thinkers of the past had some form of belief that can be termed superstitious. Of course, they were products of their times and environments, but it is always interesting to learn about the contradictions.

Take, for example, Kepler, Galileo and Newton. They were 3 important figures who laid the foundation of classical mechanics (along with many other things). But they also had their pet beliefs that were neither logical nor scientific.

In the preface of his book, Karl Popper has to say about the superstition of the 3 individuals mentioned:

Each of the three intellectual giants was, in his own way, caught up in a superstition. (‘Superstition’ is a word we should use only with the greatest caution, knowing how little we know and how certain it is that we too, without realizing it, are caught up in various forms of superstition.) Galileo most deeply believed in a natural circular motion – the very belief that Kepler, after lengthy struggles, conquered both in himself and in astronomy. Newton wrote a long book on the traditional (mainly biblical) history of mankind, whose dates he adjusted in accordance with principles quite clearly derived from superstition. And Kepler was not only an astronomer but also an astrologer; he was for this reason dismissed by Galileo and many others.

Of course, I am bringing this up not to justify any superstition. But to highlight the fact that people whom we call ‘heroes’ are humans and have their beliefs and flaws. We may derive inspiration from their work, but not all aspects of their character may be suitable for emulation.

We will have to adapt what is good and discard what is not. You may ask: what is the definition of ‘good’? Well, that is a topic for a different debate, but in this context, I would say ‘good’ are the ideas and methods developed by the abovementioned that are testable and falsifiable. Karl Popper may be happy with that definition.

Book alert – Science, Pseudoscience, and the Demarcation Problem

There is a new book (88 pages) on the philosophy of science that discusses the demarcation problem between science and pseudoscience. The topics look interesting, and have relevance in a day and age where science has been appropriated for various purposes, including spirituality.

One will have to ask how to differentiate science from something that may sound like science but, with further exploration, turns out to be a hoax?

This book tries to address this issue from a philosophical viewpoint.

The book is free to read for 2 weeks (starting 9th March 2025).

Conversation with Vinita Gowda

Vinita is a botanist and an Associate Professor at IISER-Bhopal : https://treelab.wixsite.com/tree

She and her research group work on tropical ecology and evolution of plants. Her lab specializes in plant ecology and evolution, with a focus on Zingiberaceae and Gesneriaceae. Their research interests include floral evolution, community ecology, plant-pollinator interactions, and reproductive ecology.

In the episode, we explore her intellectual journey and find how she got interested in botany via explorations in fauna and flora.

Watch/listen as we humanize science.

References:

[1]“People,” tree. Accessed: Feb. 21, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://treelab.wixsite.com/tree/people

[2]“Home,” tree. Accessed: Feb. 21, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://treelab.wixsite.com/tree

[3]“Iiser Bhopal.” Accessed: Feb. 21, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://bio.iiserb.ac.in/Home/faculty_details/1383

[4]“Vinita Gowda – Google Scholar.” Accessed: Feb. 21, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://scholar.google.co.in/citations?user=Rd6dYeIAAAAJ&hl=en

[5]“(5) Vinita Gowda | LinkedIn.” Accessed: Feb. 21, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.linkedin.com/in/vinita-gowda-5040b6153/?originalSubdomain=in

[6]“Vinita Gowda: Success has never been my weakness (@vinita_gowda) / X,” X (formerly Twitter). Accessed: Feb. 21, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://x.com/vinita_gowda

[7]“Episode 03: An Accidental Journey into the Sciences (Ft. Dr Vinita Gowda) by Scientifically Speaking,” Spotify for Creators. Accessed: Feb. 21, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://creators.spotify.com/pod/show/science-media-centre-iiser-mohali/episodes/Episode-03-An-Accidental-Journey-into-the-Sciences-Ft–Dr-Vinita-Gowda-e1l8v88

[8]Science Media Centre IISER Mohali, Science culture in India || Scientifically Speaking || Episode 03 (ft Dr Vinita Gowda), (Jul. 27, 2022). Accessed: Feb. 21, 2025. [Online Video]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EXGHD3AH1pY

[9]Science and Technology Council IISER TVM, Dr.Vinita Gowda|Why study plants? Understanding our ecosystem through plants|Green Talkies|WW’23 ESI, (Apr. 04, 2023). Accessed: Feb. 21, 2025. [Online Video]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9XCcNI-d1CE

[10]“Biodiversity,” tree. Accessed: Feb. 21, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://treelab.wixsite.com/tree/biodiversity

Listening spell-bound to Prof. Raman

This episode is based on an essay by G.V. Pavan Kumar – to be published in the journal Resonance (March 2025) arxiv preprint of the article: https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.04773

Conversation with Vivek Polshettiwar

more details here : https://sciencemeetshistory.substack.com/p/conversation-with-vivek-polshettiwar