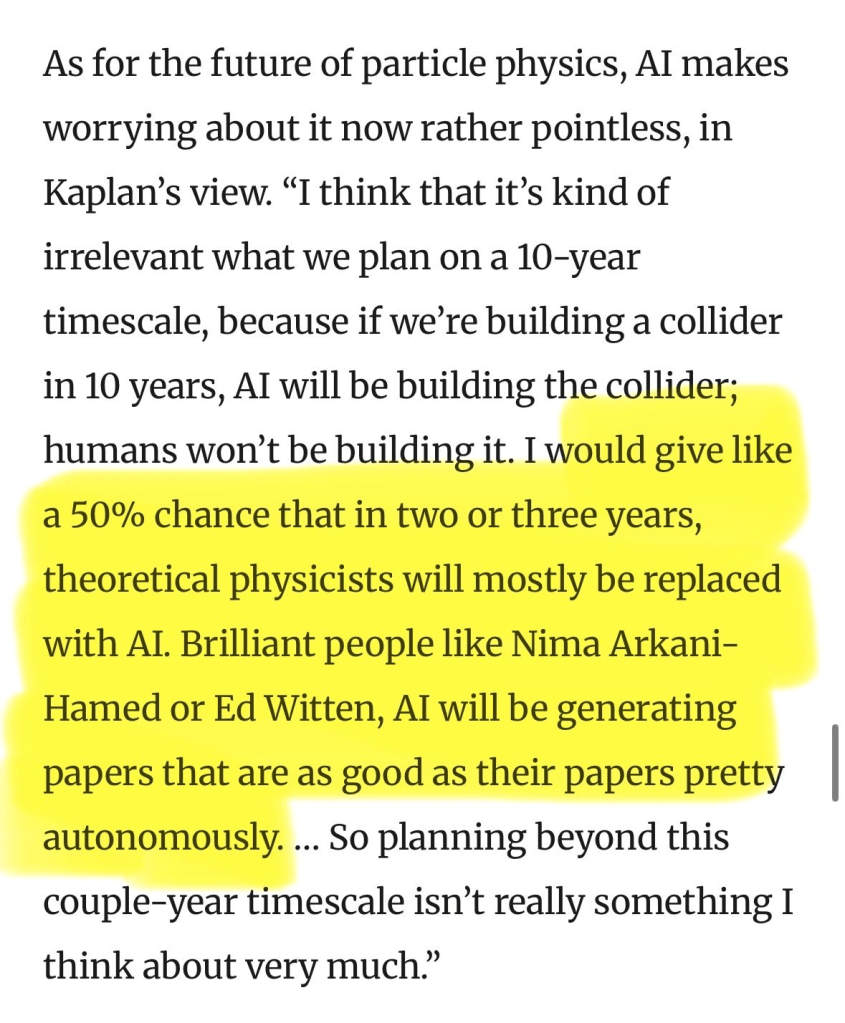

Recently, anthropic co-founder Jared Kaplan, who has a background in physics, made the following comment, which was circulated on X. Below is the excerpt:

Below is my response:

A Remarkable Human Being = Remarkable Attribute(s) + Human Being

The first term in the RHS can be replaced by AI, but not the second term, for the following reasons.

- Machines, including AI, can surely change the way humans think, work and live, but it will be difficult to match human connection. A machine can enhance human life, but can it inspire a human life?

- People inspire people. Ask a child or any adult who inspires them. It will generally be a fellow human being. Machines add value, but human beings represent a valuable life. We utilize the former, and get inspired by the latter. It is this inspiration that propels people forward to do things that may further turn out to be remarkable. This contribution is not easily quantified, but it is hard to gauge a human life without inspiration.

- People like Ed Witten, Ashoke Sen and Terry Tao add value to humanity not only through their work and ideas, but their lives show that human beings can think and do something remarkable. It assures human beings that, individually, our species can do something good.

Human beings derive meaning by interacting with fellow human beings and are inspired by the interaction. They also get inspired and draw meaning by studying people from the past. A human’s search for meaning and purpose is always in the background of other human beings. We are 8 billion plus, and it is hard to ignore each other.

It will be very unusual to find a serious student of theoretical physics who says I am inspired to live by ‘ChatGPT’.

Probably a young Kaplan, too, was inspired by a fellow human being! So, my question to Mr. Kaplan.

Who inspired you to do physics?