Writing in 1976, Weinberg made an interesting observation [1]:

A number of years ago, when I was an in-

structor at Columbia University, I heard a

rumor that Werner Heisenberg and Wolfgang

Pauli, two of the great figures in physics in this

century, had developed a new theory which

would unify the physics of elementary particles.

Thus, you can imagine my excitement when I

received an invitation to attend what was de-

scribed as a secret seminar to be conducted by

Heisenberg and Pauli. On the appointed day, I

was somewhat disconcerted to find some 500

distinguished theoretical physicists attempting to

crowd into the room; however, my enthusiasm

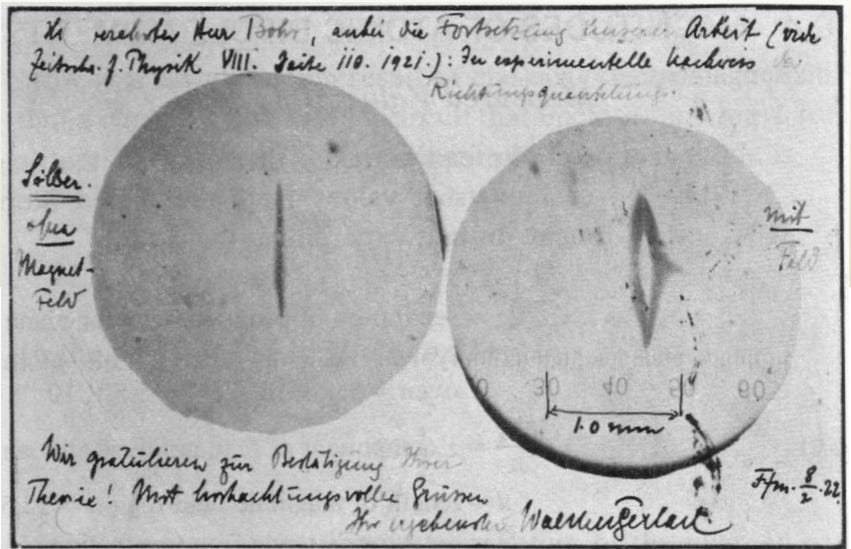

returned when I saw Niels Bohr seated in the

front row. (I had been a graduate student at

Copenhagen and had learned to look on Bohr

as an oracle.) After Heisenberg and Pauli dis-

cussed their theory, Bohr commented on it, con-

cluding that he doubted the theory would be

the great new revolution in physics because it

was not sufficiently “crazy.”

He further adds :

This remark reflects an opinion, very common among

physicists for the past forty years, that the next

significant advance in theoretical physics would

appear as another revolution – a break with the

concepts of the past as radical as the great revo-

lutions of the first third of the twentieth century:

the theory of relativity and the development of

quantum mechanics. That opinion may yet be

proved true, but what has been developing in

the last few years is, in fact, a different sort of

synthesis. There is now a feeling that the pieces

of physics are falling into place, not because of

any single revolutionary idea or because of the

efforts of any one physicist, but because of a

flowering of many seeds of theory, most of them

planted long ago

I like this way of thinking in terms of synthesis. It is closer to how science is done today than giving all the credit to an individual. Weinberg was a fine thinker who deeply thought about physics and its history. This is evident in his writing and talks.

Reference:

[1] S. Weinberg, “The Forces of Nature,” Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 13–29, 1976, doi: 10.2307/3823787.