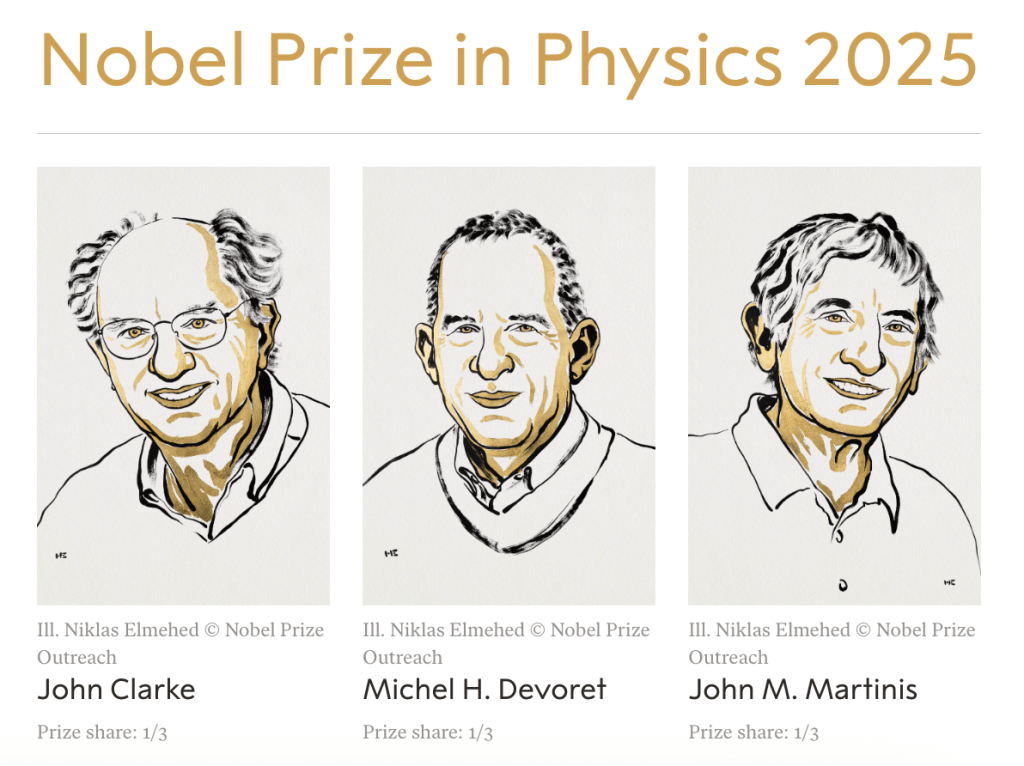

The 2025 Nobel Prize in physics has been awarded to John Clarke, Michel H. Devoret and John M. Martinis “for the discovery of macroscopic quantum mechanical tunnelling and energy quantisation in an electric circuit.“

The Nobel Prize webpage has an excellent summary of the work at popular and technical levels.

In this blog, I want to draw attention to an interesting review article from 1984 by Anthony Leggett that pre-empts the awarded work. Leggett himself was a Nobel laureate (2003), and his work on the theory of superconductors and superfluids forms one of the conceptual foundations for this year’s Nobel prize. Four of his papers have been cited by the Nobel committee as part of the scientific description of the award, and one of them is a review article I wish to emphasize.

The title of Leggett’s review is “Schrödinger’s cat and her laboratory cousins“. It discusses the detection and implication of macroscopic quantum mechanical entities, and has a description of the so-called Schrödinger’s cat, which is essentially a thought experiment describing quantum superposition and the bizarre consequence of such a formulation. Leggett utilizes this conceptual picture of the cat (in alive and dead states) and extends this to possible scenarios in which the macroscopic quantum superposition can be detected and verified under laboratory conditions. The text below from his review captures the essence of the concept and connects it to experimental verification :

“It is probably true to say that most physicists who are even conscious of the existence of the Cat paradox are inclined to dismiss it somewhat impatiently as a typical philosophers’ problem which no practising scientist need worry about. The reason why such an attitude can be maintained is that close examination of the paradox has seemed to lead to the conclusion that, worrying or not at the metaphysical level, it has at any rate no observable consequences: that is, the experimental consequences of the above apparently bizarre description are quite undetectable. Since physicists, by virtue of their profession, tend to be impatient of questions to which they know a priori no experiment can conceivably be relevant, they have tended to shrug off the paradox and leave the philosophers to worry about it.

Over the last few years, thanks to rapid advances in cryogenics, noise control and microfabrication technologies, it has become clear that the above conclusion may be over-optimistic (or pessimistic, depending on one’s point of view!). To be sure, it is unlikely that in the foreseeable future we will be able to exhibit the experimental consequences of a cat being in a linear superposition of states corresponding to life and death. However, at a more modest level it is possible to ask whether it would be possible to exhibit any macroscopic object in a superposition of states which by a reasonable common-sense criterion could be called macroscopically different. The answer which seems to be emerging is that it is almost certainly possible to obtain circumstantial evidence of such a state of affairs, and not out of the question that one might be able to set up a more spectacular, direct demonstration. This is the subject of this article.“

Cut to 2025, this is also the subject of the Nobel Prize in Physics today.

This year’s laureates, John Clarke, Michel H. Devoret and John M. Martinis, experimentally revealed the quantum mechanics of a macroscopic variable in the form of a phase difference of a Josephson Junction. They called their system a “macroscopic nucleus with wires.”

Quantum Physics Zindabad.