If you need to admire complex analysis for its elegance and visual utility, try quantum optics. Specifically, the description of quantum states. Thanks to creation and annihilation operators, the position and momentum states of a quantum optical field can be represented as quadratures. These entities can now be represented on the orthogonal axes of a complex plane. The representation of Argand diagrams starting with a classical electromagnetic field and then extrapolating them to quantum theory is a tribute to its geometrical representation. The fact that two axes can be utilized to represent real and imaginary parts of the defined state is itself an interesting thing. By certain operations within the plane, one can realize the vacuum state, the coherent state, and the squeezed state of quantum optics.

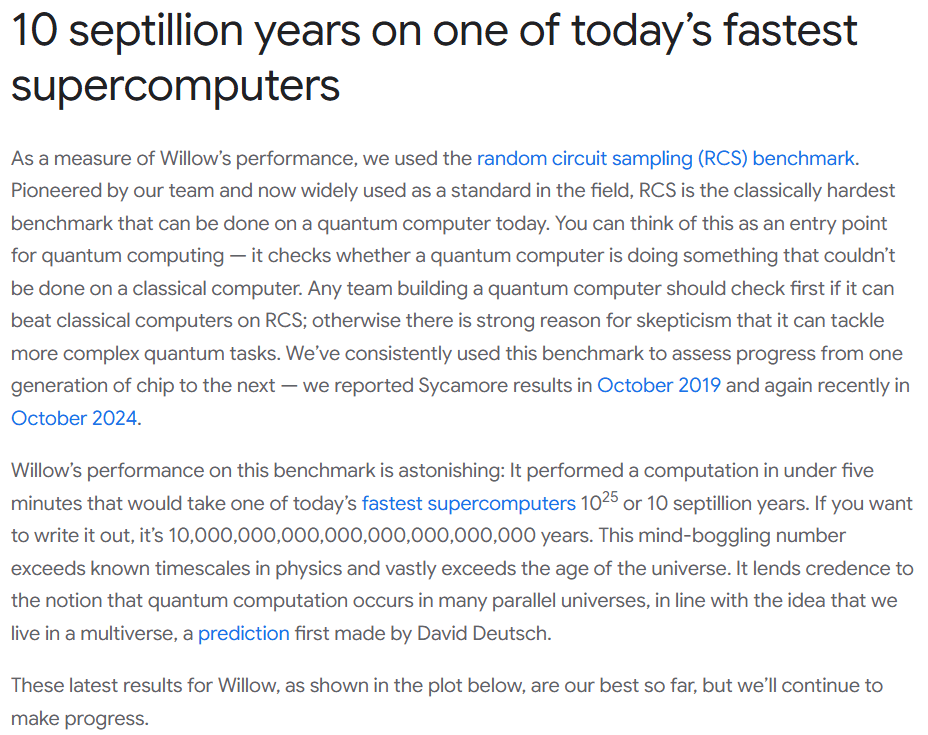

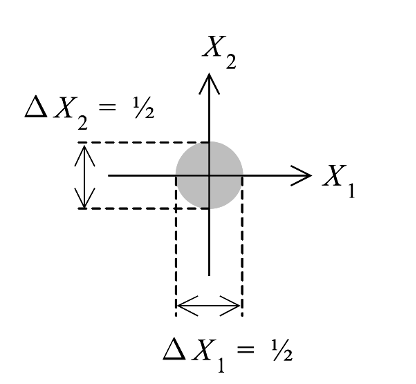

The Vacuum Spread – One of the major consequences of quantum theory, and especially the second quantization, is the realization of the vacuum states. Even when there are zero photons, there is a residual energy in the system that manifests as vacuum states. How to define the presence or absence of a photon is a different proposition because vacuum states are also associated with something called virtual photons. That needs a separate discussion. Anyway, in a complex plane of quadrature, a vacuum state is represented by a circular blob and not a point (see fig. 1). It is the spread of the blob that indicates the uncertainty. In a way, it is an elegant representation of the uncertainty principle itself because the spread in the plane indicates the error in its measurement. Importantly, it emphasizes the point that no matter how low the energy of the system is, there is an inherent uncertainty in the quadrature of the field. This also forms the fundamental difference between a classical and a quantum state. The measurement of the vacuum fluctuation is a challenging task, but one of the most prevalent consequences of vacuum fluctuation is the oblivious spontaneous emission. If one looks at the emission process in terms of stimulated and spontaneous pathways, then the logical consequence of the vacuum state becomes evident in some literature on quantum optics. Spontaneous emission is also defined as stimulated emission triggered by vacuum state fluctuations. It is an interesting viewpoint and helps us to create a picture of the emission process vis-à-vis the stimulated emission.

Figure 1. Vacuum state representation. Note that their centre is at the origin and has a finite spread across all the quadrants. Figure adapted from ref. 2.

Another manifestation of the vacuum state is the Casimir effect, where an attractive force is induced as you bring two parallel plates close to each other. The distance being of the order of the wavelength or below this triggers a fascinating phenomenon which has deep implications not only in understanding the fundamentals of quantum optics and electrodynamics, but also in the design and development of quantum nanomechanical devices.

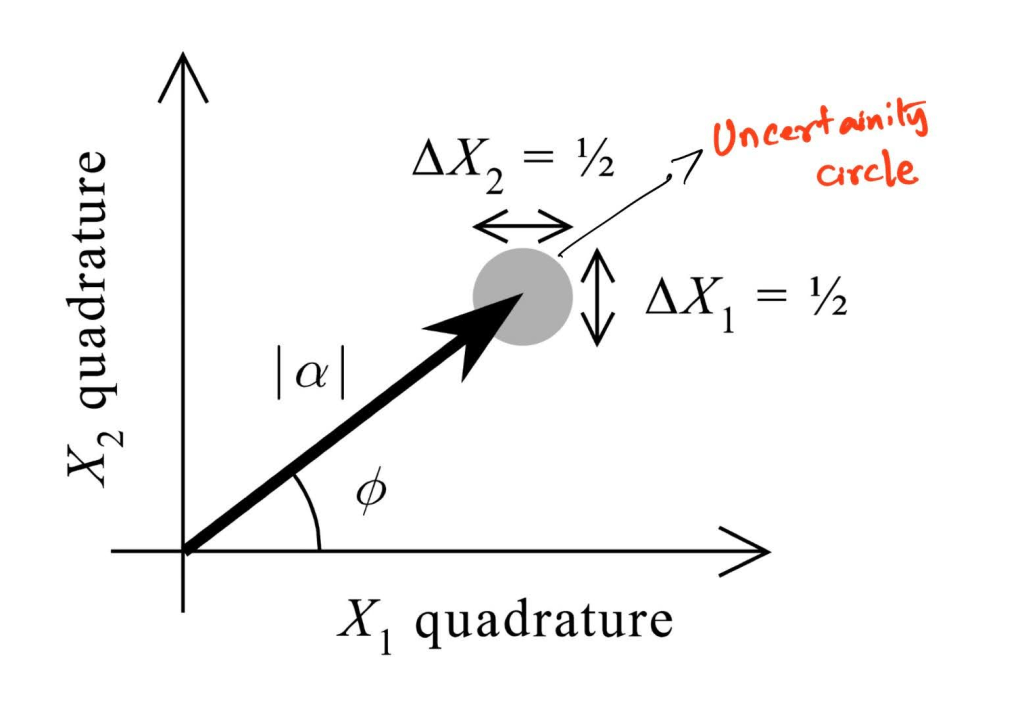

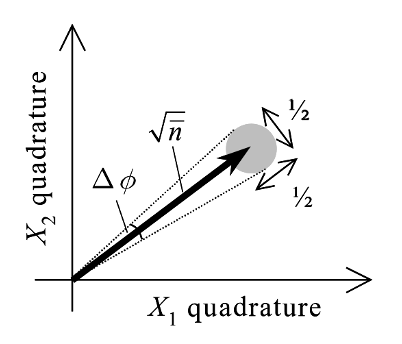

A shift in the plane – Coherent states are also described as displaced vacuum states, and this displacement is evident in the Argand diagrams. The quadrature can now help us visualize the uncertainty in the phase and the number of photons in the optical field. One of the logical consequences of the coherent state is the number-phase uncertainty. This gets clear if one observes the spread in the angle of the vector and the radius of the blob represented (see Fig. 2). Notice that the blob still exists. The only difference is that the location of the blob has shifted. The consequence of this spread has a deeper connection to the uncertainty in the average number of photons and the phase of the optical field. The connection to the number of photons is through the mod alpha, which essentially represents the square root of the average number of photons. Taken together, the blob in the Argand diagram represents the number-phase uncertainty.

Figure 2. Coherent state representation. Note that their centre is displaced. Figure adapted from ref. 2.

Lasers are the prototypical examples of coherent states. The fact that they obey Poissonian statistics is the direct consequence of the variance in the photon number, which is equivalent to the square root of the average number of photons. This means one can use photon statistics to discriminate between sources that are sub-Poissonian, Poissonian, or super-Poissonian in nature. The super-Poissonian case is the thermal light, and the sub-Poissonian state represents photon states whose number can reach up to 1 or 0. The coherent states sit in the middle, obeying the Poissonian statistics.

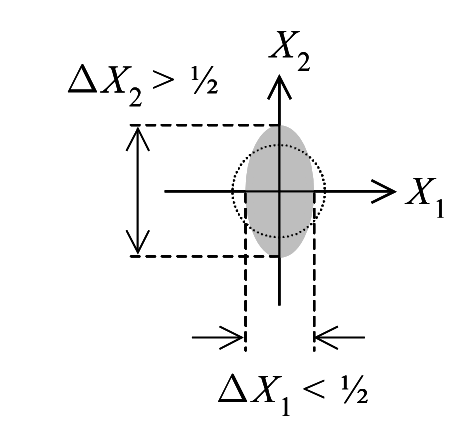

Everything has a cost – Once you have a circle with a defined area, it will be interesting to ask: Can you ‘squeeze’ this circle without changing its area? The answer is yes, and that is what manifests as a squeezed state. In this special state, one can squeeze the blob along one of the axes at the cost of a spread in the orthogonal direction. This converts the circle into an ellipse (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Squeezed State. Note the circle has been squeezed into an ellipse. Figure adapted from ref. 2.

Note that the area must be conserved, which means that the uncertainty principle still holds good; just that the reduction in the uncertainty along one axis is compensated by the increment in another. This geometrical trick has a deep connection to the behaviour of an optical field. If one squeezes the axis along the average number of photons, it means that you are able to create an amplitude-squeezed state. This means the uncertainty in the counting of photons in that state has reduced, albeit at the cost of the uncertainty in the measurement of phase. Similarly, if one squeezes the blob along the axis of the phase, then we end up with a lowering of the uncertainty for the optical phase. Of course, this comes at the cost of counting of number of photons. I should mention that the concept of optical phase itself is not clearly defined in quantum optics. This is because an ill-defined phase can have a value of 2π, which creates the problem. An interesting application of the phase-squeezed quantum states is in interferometric measurements. By reducing the uncertainty in the phase, one can create highly accurate measurements of phase shifts. So much so that this can have direct implications on high-precision measurements, including gravitational wave detection. The anticipation is also that such tiny shifts can be helpful in observing feeble fluctuations in macroscopic quantum systems.

Pictures can lead to more than 1,000 words. And if you add them to a quantum optical description, as in the case of the states that I have defined, they create a quantum tapestry. Perhaps this is the beauty of physics, where there is a coherence between mathematical language, geometrical representation, and physical reality. Feynman semi-jokingly may have said, “Nobody understands quantum mechanics,” but he forgot to add that there is great joy in the process of understanding through mathematical pictures. After all, he knew the power of diagrams.

References:

- Ficek, Zbigniew, and Mohamed Ridza Wahiddin. Quantum Optics for Beginners. 1st edition. Jenny Stanford Publishing, 2014.

- Fox, Mark. Quantum Optics: An Introduction. Oxford Master Series in Physics 15. Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Gerry, Christopher C., and Peter L. Knight. Introductory Quantum Optics. Cambridge, United Kingdom ; New York, NY, 2024.

- Saleh, B. E. A., and M. C. Teich. Fundamentals of Photonics. 2nd edition. Wiley India Pvt Ltd, 2012.