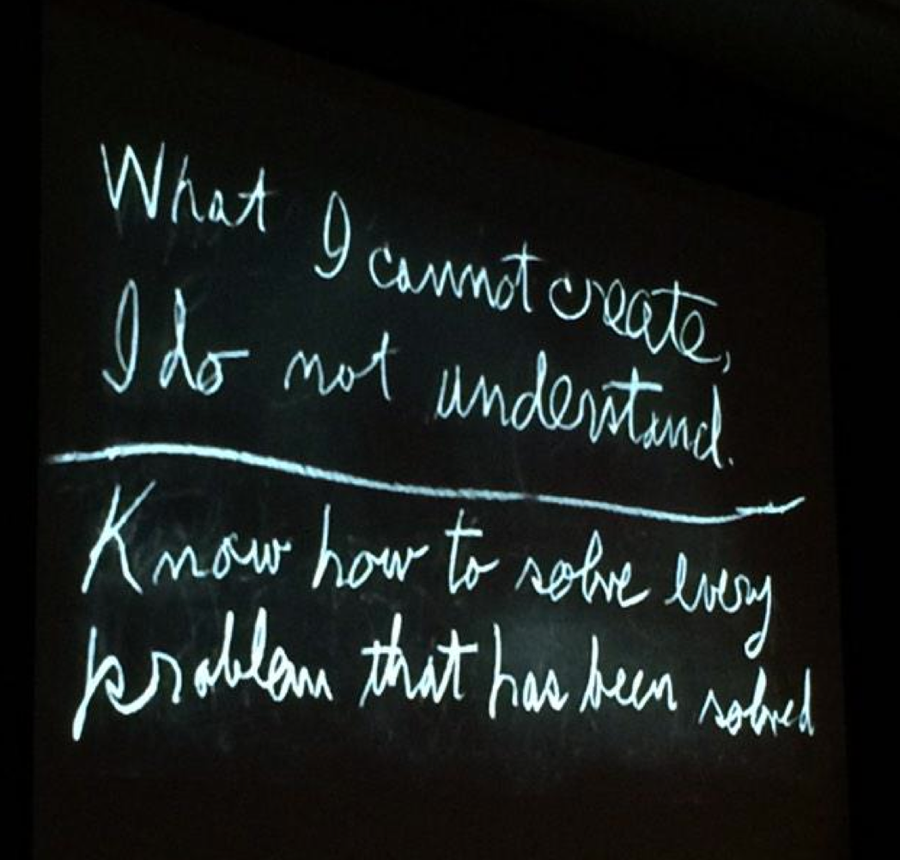

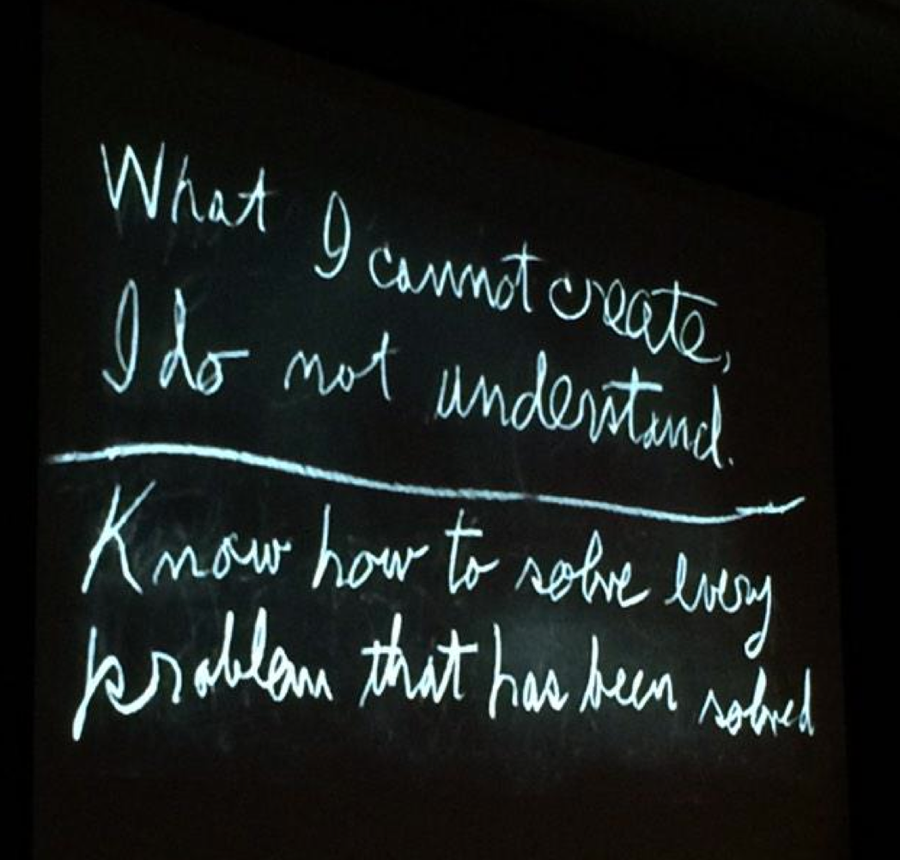

Below are two quotes on the blackboard of Feynman’s office in Caltech which were found just after his death.

Below are two quotes on the blackboard of Feynman’s office in Caltech which were found just after his death.

“…The example of great scientists is the light which guides all workers in science, but we must guard against being blinded by it. There has been too much talk about the flash of discovery and this has tended to obscure the fact that discoveries, however great, can only give effect to some intrinsic potentiality of the intellectual situation in which scientists find themselves…”

Michael Polanyi, in an essay titled “My Time with X-Rays and Crystals” (1969)

In 1972, P. W. Anderson wrote what is considered one of the most remarkable essays in the history of physics, and the title of that essay is “More is Different.” In the essay, Anderson was trying to make a case for emergence, where new, interesting physical properties can emerge by the combination of matter, which you would not anticipate if you had just kept it as an individual entity.

One of the aspects related to this essay is also the thought that reductionism has its limitations and that groups act very differently compared to individuals. The higher-level rules that can emerge from the combination of small entities are actually very different from the rules that are applicable to individual entities.

For example, if you consider electrons in a solid, you have the emergence of properties of electrons such as magnetism or superconductivity, or, for that matter, putting molecules inside a compartment and, lo and behold, life arises out of that. This has turned out to be one of the most influential ways of thinking in physics because it opened up a new avenue for understanding complex systems not as just combinations of simple systems but as the emergence of properties.

Very interestingly, this essay does not actually mention the word “emergence” at all, but the concept is so fascinating that it has turned out to be one of the most influential essays ever written in physics. The whole point about this particular essay is that the whole is more than the sum of its parts, and P. W. Anderson has to be remembered for this magnificent essay.