Read it out loud…in the age of AI..

Your voice is part of who you are..

#philosophy of #reading in this age…

Read it out loud…in the age of AI..

Your voice is part of who you are..

#philosophy of #reading in this age…

In physics, the general theory of relativity is one of the most remarkable achievements. It has turned out to be one of the most profound theories in the history of physics. In 1916, Albert Einstein proposed this theory, and it was confirmed in 1919.

Right after this confirmation, around 1920, two Indian gentlemen named Satyendranath Bose and Meghnad Saha translated Einstein’s German work into English. What you are seeing as an image is the remarkable book Principles of Relativity, containing the original papers by Einstein and Minkowski. This translation was done by M.N. Saha and S. N. Bose, who were then at the University College of Science, Calcutta University. It was published in 1920 by the University of Calcutta.

The book also contains a historical introduction by Mahalanobis, the celebrated statistician, although he was originally trained as a physicist himself. This historical introduction is itself quite remarkable.

If you look at the table of contents of this book, you will find the following:

The historical introduction discusses the evolution of ideas that led to the fruition of the general theory of relativity. This turned out to be one of the most important expositions of the general theory of relativity, soon after the emergence of the theory and its subsequent confirmation by Eddington through his famous solar eclipse expedition. This is a remarkable document, and it is available on the Internet Archive.

Jan 2026 – Apr 2026 – I am teaching a course on Quantum Optics. Below you will find some random thoughts and notes related to my reading. I will be updating the list as I go along the semester. You can add your comments below.

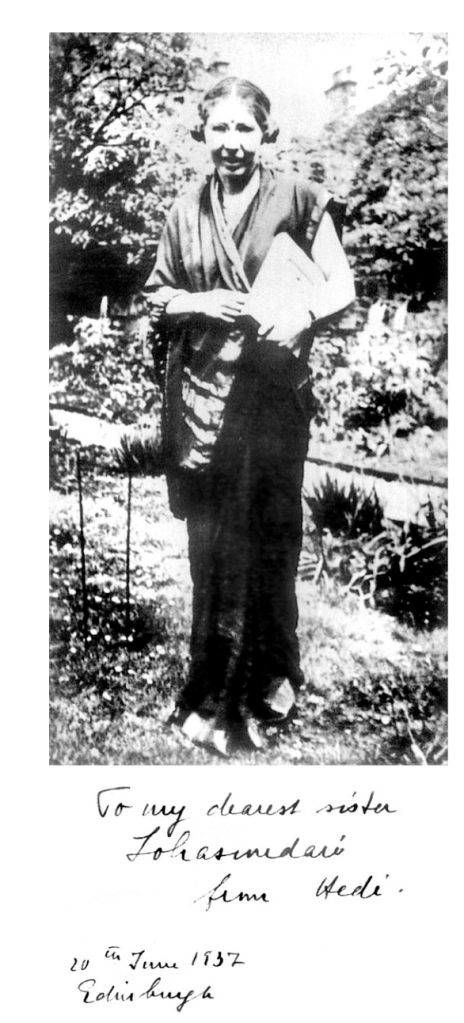

This is Hedi Born (wife of Max Born) sending a picture with a note to Lokasundari Ammal (CV Raman’s wife) in 1937.

Max Born and his family spent some time at IISc, Bangalore, in 1935-36.

Amazing to see how communication channels have changed, but the human urge to communicate remains the same..

picture source: (Venkataraman, G.; Journey into Light: Life and Science of C.V. Raman. Indian Academy of Sciences, 1989. p. 364)

Chaitanya is a professor of biology at IISER Pune and works on quantifying biology at the cellular scale. His lab focuses on cytoskeleton and cell shape research and explores synthetic biological roots to address a variety of questions at the cellular scale.

In this freewheeling conversation, we talked about quantitative biology in his lab, reading, the German language, his recent comic-themed book, and a bit on philosophy of biology as we explored his intellectual journey. Also, don’t miss the 3D model he shows to explain his research.

‘Chaitanya Athale – IISER Pune’. Accessed 3 January 2026. https://www.iiserpune.ac.in/research/department/biology/people/faculty/regular-faculty/chaitanya-athale/6.

‘Dr. Chaitanya Athale – Lab – Cytoskeleton and Cell Shape Research – Synthetic Biology’. Accessed 3 January 2026. https://sites.iiserpune.ac.in/~cathale/.

‘Chaitanya Athale – Google Scholar’. Accessed 3 January 2026. https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=Volq2gEAAAAJ&hl=en.

Chaitanya Athale | LinkedIn’. Accessed 3 January 2026. https://www.linkedin.com/in/chaitanyaa/?originalSubdomain=in.

Arias, Alfonso Martinez. The Master Builder: How the New Science of the Cell Is Rewriting the Story of Life. Basic Books, 2023.

‘Athale Lab: CyCelS 💉💉💉💉🚲🤿⛵ (@AthaleLab) / X’. 9 January 2025. https://x.com/athalelab.

link to the book on Amazon

Below are some of the discussions related to my reading and teaching:

I see that the essay I wrote on CV Raman and made open access (thanks to Resonance, which published it) has been used by several educators on YouTube, including some in Indian languages. Also, the Google AI overview shows the published essay as the main reference for a search related to Raman’s science communication (see slideshow below).

I am glad to see that making one’s writing open to all has positive effects. Open-access, not just for readers, but also for authors, is beneficial. Especially in India, paywalls for science are a detriment.

My worry is that open-access publishing has been mainly driven by commercial publishers that extract huge funds from the publishing authors. This defeats the purpose of open science, especially when the research of an author is publicly funded. Added to that, Indian researchers and writers cannot afford to pay huge sums for publishing articles and books.

The publication landscape (including journals and books) across the world needs an introspection. Open-access model is effective only when the readers and authors have access to that model. Otherwise, the model becomes a paywall for authors.

Welcome to the podcast, Pratidhavani – Humanizing Science

A. R. Venkatachalapathy is a prolific historian, writer and Professor whose work explores the social and cultural history of colonial Tamil Nadu. In 2024, he was awarded the Sahitya Akademi Award.

His notable books include “In Those Days There Was No Coffee,” “The Province of the Book,” “Tamil Characters,” and “Swadeshi Steam,” which examines V.O. Chidambaram Pillai’s role in anti-colonial maritime resistance. His scholarship spans Tamil literature, publishing history, and intellectual culture, blending rigorous archival research with literary analysis.

In this episode, we explore his intellectual journey as a historian and bilingual author.

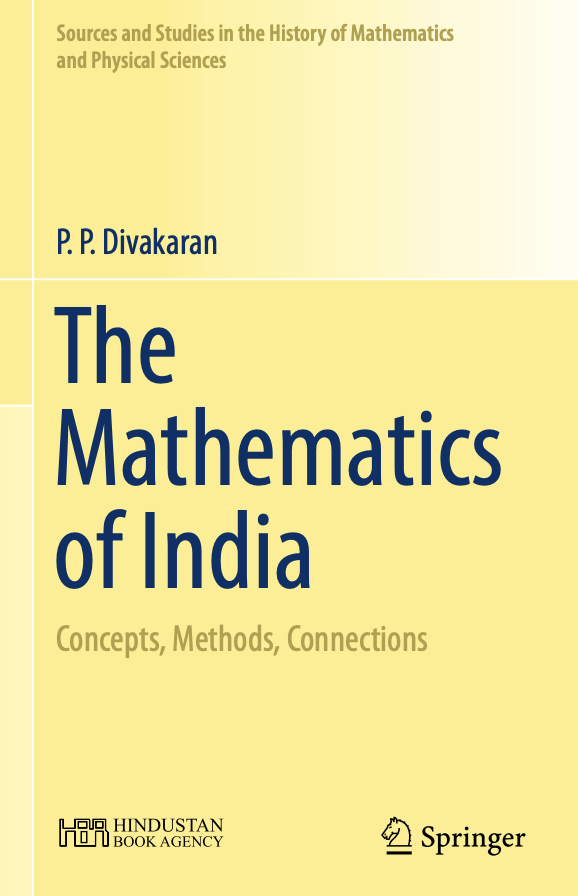

In recent years, this has been one of the best books on the history of mathematics in India. The late Prof. Divakaran was a theoretical physicist and a scholar.

This book is also an excellent example of how a scientist can present historical facts and analyse them with rigour and nuance. Particularly, it puts the Indian contribution in the global context and shows how ideas are exchanged across the geography. The writing is jargon-free and can be understood by anyone interested in mathematics.

Unfortunately, the cost of the book ranges from Rs 8800 to Rs 14,000 (depending on the version), which is a shame. Part of the reason why scholarly books, particularly in India, don’t get the traction is because of such high cost. This needs to change for the betterment and penetration of knowledge in a vast society such as India.

There is a nice video by numberphile on Prof. Divakaran and his book: