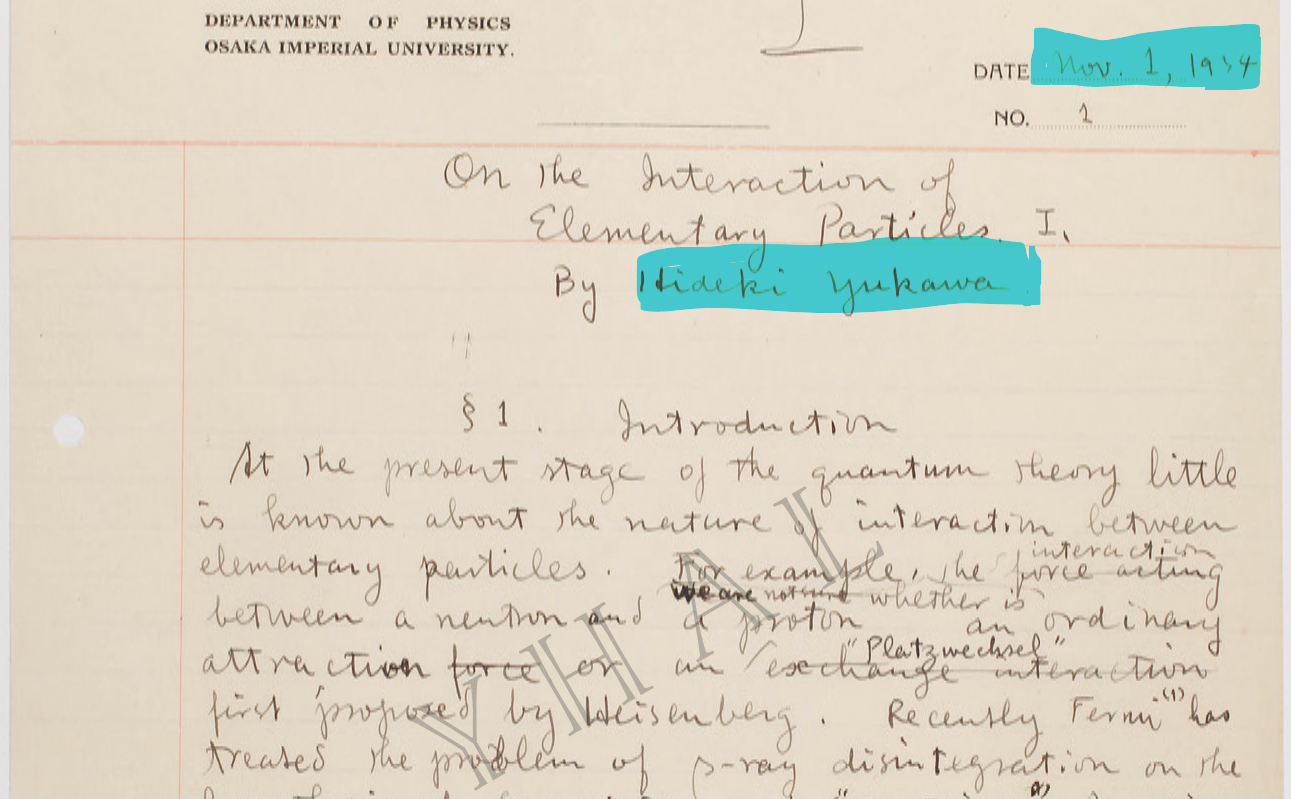

I have been amazed to explore the archives on Hideki Yukawa, which have been systematically categorized and meticulously maintained by Osaka University in Japan. My sincere thanks and acknowledgment to the Yukawa Memorial.

Below are a few gems from their public archives :

- Draft of the paper written in 1934 – The making of the groundbreaking paper of Yukawa, which eventually led to his Nobel Prize in 1949.

The archive draft is accompanied by a note which reads:

Yukawa had not published any paper before then. In 1933, Yukawa began working at Osaka Imperial University and tackled the challenge of elucidating the mystery of nuclear forces while Seishi Kikuchi and other prominent researchers were producing achievements in nuclear physics and quantum physics. The idea of γ’ (gamma prime) that Yukawa came up with in early October led to the discovery of a new particle (meson) that mediates nuclear forces. The idea of introducing a new particle for the purpose of explaining the forces that act between particles was revolutionary at that time. Yukawa estimated the mass of the new particle and the degree of its force. No other physicists in the world had thought of this idea before.

2. Letters between Tomonaga and Yukawa

Sin-Itiro Tomonaga was a legendary theoretical physicist from Japan, who independently formulated the theory of quantum electrodynamics (apart from Feynman and Schwinger) and went on to win the Nobel Prize in physics in 1965.

Tomonaga was a friend and classmate of Yukawa, and they inspired each other’s work. Below is a snapshot of the letter from 1933 written in Japanese.

Both these theoreticians were intensely working on interrelated problems and constantly exchanged ideas. The archival note related to the letter has to say the following:

During this period, Yukawa and Tomonaga concentrated on elucidating nuclear forces day in and day out, and communicated their thoughts to each other. In this letter, before starting the explanation, Tomonaga wrote “I am presently working on calculations and I believe that the ongoing process is not very interesting, so I omit details.” While analyzing the Heisenberg theory of interactions between neutrons and protons, Tomonaga attempted to explain the mass defects of deuterium by using the hypothesis that is now known as Yukawa potential. The determination of potential was arbitrary and the latest Pegrum’s experiment at that time was taken into consideration. Tomonaga also compared his results with Wigner’s theorem and Majorana’s theory.

3. Rejection letter from Physical Review

Which physicist can escape a rejection from the journal Physical Review?

Even Yukawa was not spared :-) Below is a snapshot of a rejection letter from 1936, and John Tate does the honours.

The influence of Yukawa and Tomonaga can be seen and felt at many of the physics departments across Japan. Specifically, their influence on nuclear and particle physics is deep and wide, and has inspired many in Japan to do physics. As the archive note says:

Yukawa and Tomonaga fostered the theory of elementary particles in Japan from each other’s standpoint. Younger researchers who were brought up by them, so to speak, must not forget that the establishment of Japan’s rich foundation for the research of the theory of elementary particles owes largely to Yukawa and Tomonaga.

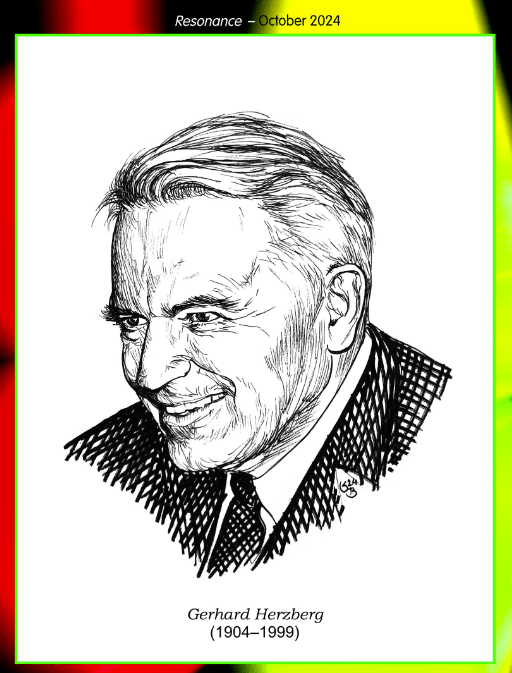

4. Lastly, below is a picture of the legends from the archive: Enrico Fermi, Emilio Segrè, Hideki Yukawa, and James Chadwick.

From the archive note on the picture from September 1948:

Yukawa met Prof. Fermi and other physicists of the University of Chicago who were staying in Berkeley for the summer lectures. From the left: Enrico Fermi, Emilio Segrè, Hideki Yukawa, and James Chadwick.

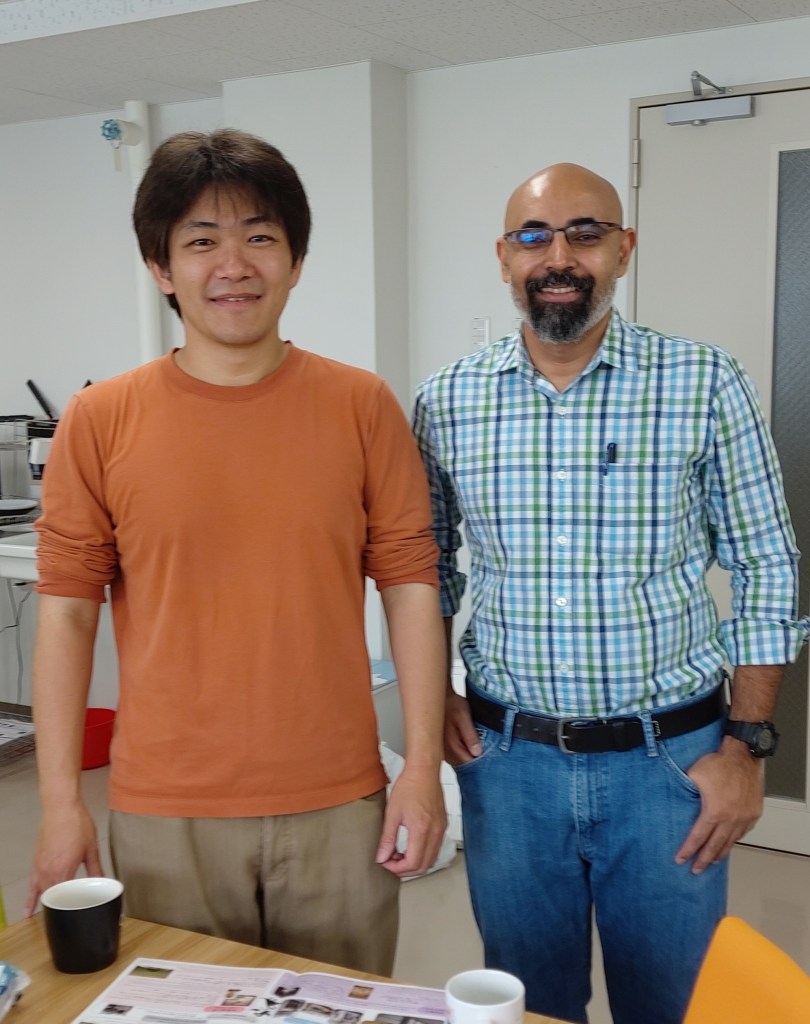

Tomorrow, I will conclude my third trip to Japan. I always take a lot of inspiration from this wonderful country. As usual, I have not only met and learnt a lot from contemporary Japanese researchers, but also have metaphorically visited the past masters who continue to inspire physicists like me across the world.

For this, I have to say: Dōmo arigatōgozaimasu !