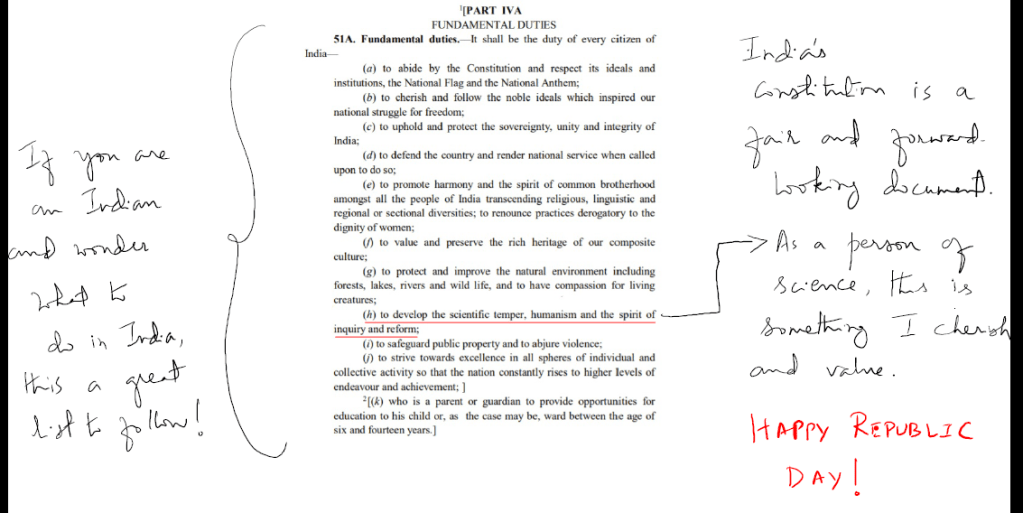

link to The Constitution of India: https://legislative.gov.in/constitution-of-india

link to The Constitution of India: https://legislative.gov.in/constitution-of-india

“The physicist is most cogently identified, not by the subject studied, but by the way in which a subject is studied and by the nature of the information being sought.”

Above is an interesting quote by Sol Gruner, James Langer, Phil Nelson, and Viola Vogel from a 1995 article in Physics Today titled WHAT FUTURE WILL WE CHOOSE FOR PHYSICS?

Although written more than 25 years ago from the viewpoint of US physics community, many of the issues discussed in this article are pertinent even today. Probably more so in the Indian context.

Nice read :

What Future Will We Choose for Physics?

Sol M. Gruner, James S. Langer, Phil Nelson, and Viola Vogel

Citation: Physics Today 48, 12, 25 (1995); doi: 10.1063/1.881477

View online: https://doi.org/10.1063/1.881477

IIA days…

It was late summer/early monsoon season of 2003, in Bangalore. The BTS bus travel from Rajajinagar to Koramangala via Majestic used to take 90 min or more. This commute, which I did for about 2 to 3 months, as summer student at Indian Institute Astrophysics (IIA) is still etched in my memory. I had just finished my first year MSc (Physics), and was seriously hooked on to physics in general, and astrophysics in particular. My summer project was on second solar spectrum guided by Prof. K. N. Nagendra (KNN) at IIA. It was he who introduced me to the fabulous world of polarization optics in the context of solar physics. This opened my eyes to the spectacular world of photon transport through an inhomogeneous medium, and hence multiple scattering of light. It was KNN who also introduced me to the classic : Radiative Transfer by Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar. My first task as a summer student was to read the first chapter of this book and understand the representation of polarized light using Stokes parameters. The summer of 2003, was also the first time I encountered the power of computational methods to solve scientific problems, and ever since then I have deeply appreciated the role of computers in solving scientific problems. This introduction to computational physics and polarization optics (in the form of Jones, Stokes and Muller matrices) has turned out to be an important concept which I still use in my research. I thank KNN for this.

Recently, I was shocked to know that Prof. KNN passed away. His death was untimely, and a very sad news to me and many of the people who knew him. My condolences to his family, friends and students.

Weinberg inspires…

Recently, I also came to know about the sad demise of Steven Weinberg. Thanks to a special paper on Introduction to Quantum Electrodynamics in the final semester of my MSc, I learnt a bit about Weinberg as we were introduced to some aspects of unification of weak and electromagnetic forces. Also, with great enthusiasm, I learnt a lot from his fascinating book : The First Three Minutes: A Modern View of the Origin of the Universe. Undoubtedly, the scientific world has lost a great thinker.

The greatest impact of Weinberg on me was in a different context. In summer of 2004, I was selected for a PhD position at JNCASR. Prof. Chandrabhas had agreed to take me in as a PhD student, and I was elated and excited to join his group. I still remember the first time I visited his lab (after the selection) sometime in late May or early June 2004. As I entered the lab and opened that famous sliding door, there was a print-out of an article which was pasted right beside the door. This article was the Four Golden Lessons by Steven Weinberg, which was then recently published in 2003. This was literally, the first article I read as a PhD student in the lab, and has deeply impacted my work.

I still revisit the four golden lessons, time and again, and has been extremely useful throughout my career. As a tribute to him, below I reproduce the third lesson, which I think is worth contemplating :

My third piece of advice is probably the hardest to take. It is to forgive yourself for wasting time. Students are only asked to solve problems that their professors (unless unusually cruel) know to be solvable. In addition, it doesn’t matter if the problems are scientifically important — they have to be solved to pass the course. But in the real world, it’s very hard to know which problems are important, and you never know whether at a given moment in history a problem is solvable. At the beginning of the twentieth century, several leading physicists, including Lorentz and Abraham, were trying to work out a theory of the electron. This was partly in order to understand why all attempts to detect effects of Earth’s motion through the ether had failed. We now know that they were working on the wrong problem. At that time, no one could have developed a successful theory of the electron, because quantum mechanics had not yet been discovered. It took the genius of Albert Einstein in 1905 to realize that the right problem on which to work was the effect of motion on measurements of space and time. This led him to the special theory of relativity. As you will never be sure which are the right problems to work on, most of the time that you spend in the laboratory or at your desk will be wasted. If you want to be creative, then you will have to get used to spending most of your time not being creative, to being becalmed on the ocean of scientific knowledge. (emphasis is mine)

Thank you, KNN and Weinberg…for some golden lessons…

Thanks to Gautam Menon, I came across this article in Nature, which makes an interesting case for being self critical of one’s own published work.

Perhaps, this is a good way to go, although much easier said than done. Overall, I strongly support the line of thinking of looking inward and being critical of one’s work.

One of the motivations for writing my blog is to highlight the human element of doing science, and honest mistakes in the pursuit of science are very much part of it.

This is indeed a good culture to inculcate and encourage in a day and age where everything negative and critical is looked down upon as a disadvantage.

The article also reminds me of Peter Medawar’s talk: “Is the scientific paper a fraud?” , which was one of the most refreshing viewpoints on the pursuit of science that I have read. Interestingly, there has been quite a lot of debate on this question, and is worth exploring.

Also there is an element of Gandhism in being truthful to oneself and others, which is refreshing to see in scientific world :-)

Central to scientific thinking is the ability to create an idea, test it rigorously, and report the results. This thinking is made coherent and expressed in the form of writing. Scientific research indeed can be fostered and improved by writing well, especially when guided by the goals to achieve accuracy and clarity.

I recently read a wonderful article by Prof. Raghavendra Gadagkar, which elegantly makes a case for why scientist must write to a wider audience, and why the boundary between the roles of a scientist and a science writer should be diminished.

The article reads like a manifesto for science communication, as the author himself states at the end. I strongly recommend this article to anybody who is involved in pursuit of science.

Perhaps I will add one more point to what the author mentions. There might be a very important role for science writers who can take emerging developments in science literature and translate it into vernacular language. An authentic scientific voice in regional language can really impact not only the interest of students, but also of the general public, including policy makers and politicians.

India and the world needs more science, and scientific way of life. Therefore, doing science is as important as communicating it. Prof. Gadagkar’s article makes an excellent case for this.

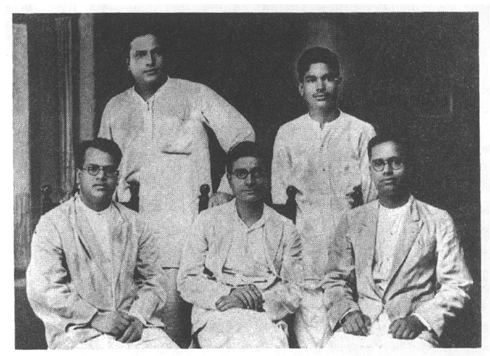

Above picture : A group of 5 students of Raman. Front row- Left to Right 1) S. Vekateswaran, whose observations on the polarized ‘weak fluorescence’ of glycerine in early 1928 started the last lap of investigations which led to the discovery of the Raman effect. 2) K. S. Krishnan, he was 31 when this photograph was taken. 3) A. S. Ganesan – spectroscopist, later editor Current Science, who worked with Raman. He compiled the first bibliography of the Raman effect which Rutherford submitted to the Nobel Committee when he proposed Raman for the Nobel Prize. Back row. 1) C. Mahadevan, who later became renowned geologist who did his post-graduate work with Raman on X-ray studies of minerals. He was present at the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science in Calcutta during the momentous discovery of the Raman effect and he has left graphic accounts of what happened then. Right S. Bhagavantam, another renowned student of Raman, who worked with him after the discovery of the Raman effect and is well-known for his application of group theory to the Raman effect. Reproduced from Current Science, Vol 75, NO. 11, 10 DECEMBER 1998

Today is National Science Day in India. We celebrate this day in commemoration of the discovery of the Raman effect. I have previously written about the significance of this day.

One of the important aspects of the discovery of the Raman effect is the role played by the then student K.S. Krishnan, who went on to be become a distinguished scientist and the founding Director of National Physics Laboratory, Delhi. There were also a few others who played a part in this discovery too (see picture)

Raman Research Institute has an excellent repository of the collected works of Raman. It also has a lot of content about Raman.

Of the many documents, the one which caught my attention was an interview of K.S. Krishnan by S. Ramaseshan, which was published in Current Science. Below I reproduce a few excerpts from the article:

“I (Ramaseshan) said there was a view that he (Krishnan) years discovered the Raman effect for Raman and this view had again surfaced. His reply was ‘It is a blatant misrepresentation. The best I can say is that I participated actively in the discovery”

Krishnan goes on to say how it all started with Raman taking the initiative. In fact, Krishan vividly describes the scene :

‘The story starts in the early Febrauary 1928 when Professor (Raman) came to

my room and said “I want to pull out of the theoretical studies in which

you have immersed yourself for the 2 or 3 years. I feel it is not quite healthy

for a scientific man to be out of touch with actual experimentation and experimental facts for any length of time’

Interestingly, Raman and Krishan fell out of each other, and this interview has some snippets of this controversy. The article has some comments by S. Chandrasekhar on the credit of discovery behind Raman effect, in which he attributes Raman and Krishan’s collaborative approach towards the discovery, and mentions about the importance of exchanging ideas between two researchers working on a problem.

Overall, I must mention that the interview and the historical anecdotes in the document are riveting to say the least, and also showcases the complexity and sociology of a scientific discovery.

Science, per se, is objective. But pursuit of science has a human element, which makes it complex and interesting…

So always remember that as we commemorate the effect named after a person, but there are a few more people who have contributed to it. After all, science is a collective human endeavor.

Happy Science Day !

As student of science and as a practicing researcher one can always ask why should we do science?

If you look at this question from an utilitarian viewpoint, especially in times where vaccination is in the news (for right and wrong reasons), one does not need to give strong justifications for doing science. Its relevance is there to see in our lives and its impact is it ubiquitous.

So, do scientists always think about an application while doing science? The answer is : not always.

In fact many important discoveries and inventions in science, even those which turn out to have huge applications, were not envisaged with an application in mind.

An illustration of this aspect is beautifully communicated in the above video by Prof. P. Balaram, who is an excellent scientist at IISc, and also served as its director in the past.

I should mention that during my PhD course work days, I had the privilege of taking professor Balram’s molecular spectroscopy course in the molecular biophysics unit of IISc.

Being a student of physics I was introduced to the fascinating concepts of molecular spectroscopy from biophysics and biochemistry viewpoint. I learnt a lot about molecules, their stereochemistry and their interaction with light in this fantastic course. Even to date, when I think about chirality in the optical physics, some of the lessons learnt during this course has come extremely handy. Undoubtedly this was one of the best courses I have attended.

General advice, especially for students in physics, is in order to get a deeper intuition in physics it is good to study some fundamental aspects in chemistry and biology. For sure ones understanding of concepts such as chirality and symmetry is enriched if we look at these topics from the chemistry and biology viewpoint.

Similarly students of chemistry and biology can get a deeper insight into the structure and dynamics of molecules if they understand the nature of light in the context of polarization, phase and momentum etc.

After all the universe we live in does not discriminate between the disciplines we used to study it…

Michael V. Berry is a distinguished theoretical physicist. He has made outstanding contribution towards classical and quantum physics, including optics (Pancharatnam-Berry phase, caustics, etc.). Berry is also a prolific writer and commentator on science and its pursuit. Recently, I came across a foreword published on his webpage, that I think is provocative but worth reading..here is a part of it :

“At a meeting in Bangalore in 1988, marking the birth centenary of the Nobel Laureate C V Raman, I was asked to give several additional lectures in place of overseas speakers who had cancelled. During one of those talks, I suddenly realised that underlying each of them was one or more contributions by Sir George Gabriel Stokes. Understanding divergent series, phenomena involving polarized light, fluid motion, refraction and diffraction by sound and of sound, Stokes theorem (I didn’t know then that he learned it from Kelvin)…the list seemed endless.

My enthusiasm thus ignited, I acquired Stokes’s collected works and explored the vast range and originality of his physics and mathematics (separately and in combination). Paul Dirac was certainly wrong in his uncharacteristically ungenerous assessment (reported by John Polkinghorne), dismissing Stokes as “… a second-rate Lucasian Professor”. On the contrary, in every subject he touched his contributions were definitive, and influenced all who followed. Perhaps Dirac failed to understand, as we do now, that discovering new laws of nature is not the only fundamental science: equally fundamental is discovering and understanding phenomena hidden in the laws we already know…………..”

An important takeaway is that fundamental science can also evolve as a consequence of existing laws applied to new boundary conditions or systems. In an essence, Berry’s comment also resonates with PW Anderson’s argument on emergence, which laid a philosophical foundation and integrated science of condensed matter. Undoubtedly, Stokes made some profound discoveries in physics, and a recent book illustrates his science and life (Berry’s foreword is from the same book).

post script: in the year 2000, Berry shared the IgNobel prize, with Andre Geim, for magnetic levitation of frogs. As you may know, Geim went on to win the Nobel prize in Physics (2010) for his groundbreaking work on graphene.

Will Berry get a Nobel prize in 2020 ? He is certainly a deserving candidate…we will see on 6th Oct…

When I come across any book, I do two things : first, I take a glimpse at table of contents, and second, I read the preface/foreword to the book. The second part is generally revealing in its own way, as I get to learn not only about the content of the book, but also about the human side of the topic under study. Recently, I was reading a technical book. In there, I came across a foreword written by Jacques Friedel, in which he quotes his grandfather Georges Friedel, and a part of the quoted text is reproduced below :

…none of the three approaches – the naturalist, the physicist, and the mathematician – should be neglected and that a healthy balance must be preserved amongst them !……

The text in bold is my emphasis. This quote resonates with what I think is a good way of doing science. Let me elaborate a bit on this “trinocular” view of science.

Image courtesy : Pexels – Creative Commons License

What I have discussed above is a way (not the only way) to approach research in natural science. Interestingly, the above 3 approaches need not be considered in chronological order. The inspiration to study a natural phenomenon or anything for that matter can be initiated from any of the 3 approaches. A question or an observation in any one framework can be cast as a query in any other framework, and that is what makes pursuit of science so wonderful.

Perhaps, the most important lesson from the Friedel’s quote is to keep a healthy balance of all the three approaches while studying a natural process. Importantly, this triangulation and extrapolation of approaches is how you build knowledge : be it engineering, medicine, public policy or any facet of epistemology. At the heart of all these approaches is to look at a problem from multiple viewpoints and be open to adaptation, criticism, and revision.

After all, depth in view needs more than one cue !

Image: Pixabay (creative common license)

Recently, I read an article titled The Quantum Poet. It is about Amy Catanzano, an academic poet amalgamating poetry with quantum physics. What is impressive is that she is trying to create a platform to communicate emerging trends in quantum world through poetry. She thinks poetry can bring something unique in terms of presentation which may help us understand science in a better way. In her own words she describes the power of poetic presentation :

“Poetry is a nuanced and complex form of language that goes beyond simple dictionary definitions of individual words. Poems use rhythm, visual structure, line breaks, word order, and other devices to explore invisible worlds, alter the flow of time, and depict the otherwise unimaginable”

Attempts to bring science and poetry together is an active effort now, as evidenced by projects such as “The Universe in Verse”, which is an emerging platform where scientist and poets not only exchange ideas but also get together to create something new. An early proponent of this philosophy is the poet Ursula K. Le Guin, who describes beautifully why science and poetry are necessary to understand the world that is overloaded with information :

“Science describes accurately from outside, poetry describes accurately from inside. Science explicates, poetry implicates. Both celebrate what they describe. We need the languages of both science and poetry to save us from merely stockpiling endless “information” that fails to inform our ignorance or our irresponsibility.”

Whereas the above examples show how poets are embracing science, I should mention that scientist too have been active in this endeavor. Roald Hoffmann, the Nobel prize winning chemist is one of the great examples of this.

The combination of science and poetry has interesting connection in ancient Indian tradition too. Specifically, many of the Sanskrit surtras essentially do this as evidenced in some old Indian texts. If you want to know more, I suggest you read this article by Roddam Narasimha. His work, in my opinion, is a reliable source on topics related to science in ancient India. Interestingly, many languages in India do combine poetry with puzzles. One example that immediately comes to my mind is a lyrical puzzle in Kannada by Purandara Dasa called Mullu koneya mele.

A famous essay by C.P. Snow titled “Two Cultures” observed that arts and science, which are two endeavors of human activities, have to come together for a richer intellectual human experience. A lot has been debated on this topic. Perhaps, the above examples show that the two cultures indeed can inspire each other to create something neither of them can create individually. Of course, there is still a lot to achieve in this direction.

Science, arts and sports are three pursuits of human beings which are integral parts of our lives. Personally, I cannot imagine a world devoid of them. Let me conclude with a small poem I wrote sometime ago (this is a modified version that I had posted on facebook) :

Cycles of thought set question into motion,

it pours meaning into life as a cerebral conception.

Fathering an idea: a borrowed perception;

no endeavor is original, everything an inception.

Science, Arts and Sports are facets of inspiration;

after all, what is life without their juxtaposition.

ps : Disheartening to know the passing away of Indian actors Irrfan Khan and Rishi Kapoor. A lot of people are sad… reinforces the importance of art and artists in human society.