How do you determine the refractive index of a material which is not transparent?

In 1895, J.C. Bose addressed this question experimentally using ‘electric rays’, which we currently know as microwave radiation!

The citation of the paper is

Bose, J. C., I. On the determination of the indices of refraction of various substances for the electric ray. I. Index of refraction of sulphur. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, 59(353–358), 160–167. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspl.1895.0069

Below is the title of the paper that was communicated to the Royal Society via Lord Rayleigh, who was an authority on optical concepts Bose was using.

His experiment used the microwaves’ total internal reflection and extracted the samples’ refractive index through Brewster’s angle.

Bose beautifully describes his method as follows :

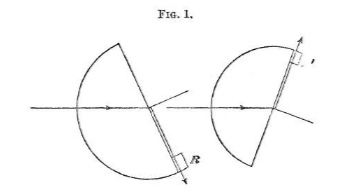

The angle of incidence is slowly decreased till the critical value is reached. At this point the ray is all at once refracted into the air, making an angle of 90° with the normal to the surface. If a receiver be fixed against the side of the semi-cylinder at II, it will now respond to the refracted radiation.

Below is the diagram depicting the same principle :

And the detailed description is as follows:

The refracting substance is cut out or cast in the form of a semi¬ cylinder, and mounted on the central table of a spectrometer; the electric ray is directed towards the centre of the spectrometer, and its direction is always kept fixed. It strikes the curved surface and passes into its mass without any deviation. It is then incident on the plane surface of the semi-cylinder, and is refracted into the air beyond.

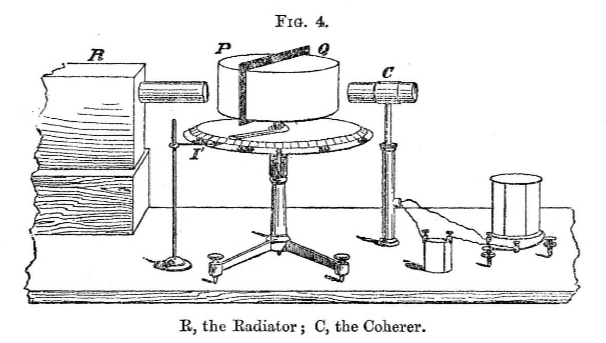

The apparatus design was also interesting, and the diagram below depicts what we nowadays call the microwave transmitter (indicated as radiator, R) and receiver (indicated as Coherer, C).

If you read the paper completely, the details of experiments are described meticulously, and the attention to detail is remarkable.

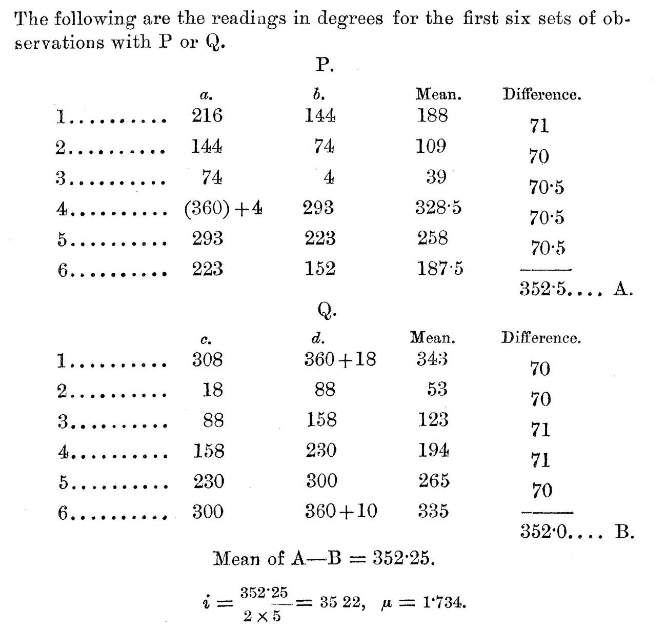

So, he determines the refractive index of sulfur using this method and ends up with a value of 1.734, which is quite accurate even by today’s standards (the value is upwards of 1.7 and depends on the wavelength of light). Notice that the measurement was made to the accuracy of three decimal places, which is impressive. Below is a set of data for which the value of the refractive index was determined.

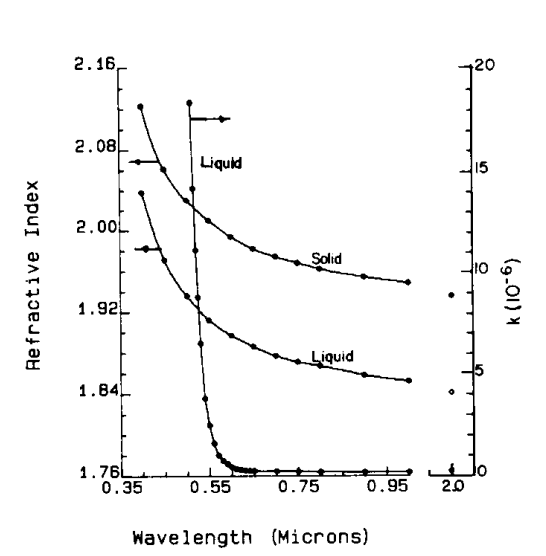

Now compare this to the modern measurement (see below data from around 1985) of refractive index based on more sophisticated methods, and you will see the matching is reasonably good at higher wavelengths close to 1 micron. (Note that Bose’s measurements was at higher wavelength than shown below)

J.C. Bose was a creative scientist; the above example is just a small illustration of his capabilities as an experimentalist.

Now, with this inspiration, let me head back to my lab to do some experiments :-)

ps: A video to go with this blog (updated on 17th Apr 2025)