Ramaseshan on Raman

(from G. Venkataraman, Journey into light: life and science of C.V. Raman. Indian Academy of Sciences in cooperation with Indian National Science Academy, 1988)

Ramaseshan on Raman

(from G. Venkataraman, Journey into light: life and science of C.V. Raman. Indian Academy of Sciences in cooperation with Indian National Science Academy, 1988)

Recently, there has been a buzz about a Nature paper titled Evidence for chiral graviton modes in fractional quantum Hall liquids. There has been some media reportage on the paper too.

The paper makes interesting claim on observation of ‘chiral graviton modes’ in certain ultra-cooled semiconductors (Gallium Arsenide – famously called GaAs). The cooled temperature is quite low (~50 mK), which is impressive, and the chirality of the mode is unveiled using polarization-resolved Raman scattering. The observation of this so-called ‘Graviton modes’ is essentially a quasiparticle excitation, and has created some buzz. In my opinion, graviton-like behavior is a bit of an exaggeration.

Anyway, this paper has set an interesting discussion among my colleagues (condensed matter and high energy physics) in our department. To add to their discussion, I wrote on 2 points (and an inference) from optics perspective, which I am sharing below :

2. The last author of this paper, Aron Pinczuk, was a well-known expert in light scattering in solids. He was an Argentinian-American professor at Columbia University, and passed away in 2022.

He and the legendary Manuel Cardona were instrumental (pun intended) in laying the foundation for using inelastic light scattering methods in solids. The first edition of the series “Light Scattering in Solids”, written in 1976, has Pincuk discussing the very measurement scheme used in the paper (see picture).

My initial inference on the paper : This is an old Argentinan wine of quasiparticles in a new GaAs bottle at ultra-low temperature….and NATURE is selling it as champagne de graviton made in China !

Isaac Asimov is undoubtedly one of the greatest science fiction writer in English. He also wrote a lot of non-fiction science books that are interesting and accurate in their exposition. I recently came across an interesting book by him on lasers. Written around 1990s, this book discusses the origins of lasers and the basic physics and engineering aspects of lasers. True to his reputation, he weaves interesting history into the science, that makes an engaging read. Some grayscale (charcoal-kind) illustrations in the book are appealing, and makes it a smooth read.

The book also has a short discussion on applications of lasers, and eye surgery is one of them which is explained lucidly.

If you are not from a scientific background, or want to have a light read on lasers, then I would recommend this book. As usual, Asimov does not disappoint you !

Asimov was a biochemistry professor before he became a full time writer. His incliniation towards chemistry is evident when he discusses ‘chemical laser’. I reproduce a couple of paragraphs from his book:

This idea of the so called ‘chemical laser’ is still under exploration, and has not found its full potential. Perhaps there is an interesting research problem here for the interested.

Internet archives has a link to this book, but it is not complete. On the internet, you may find other links to this book.

What was surprising to me is that I found a Marathi translation of this book online. I don’t know how good is the translation, but I will urge you check it out if you know the language well.

Asimov was a unique person, as he blended science, storytelling and writing very efficiently. We need more of his kind in this world.

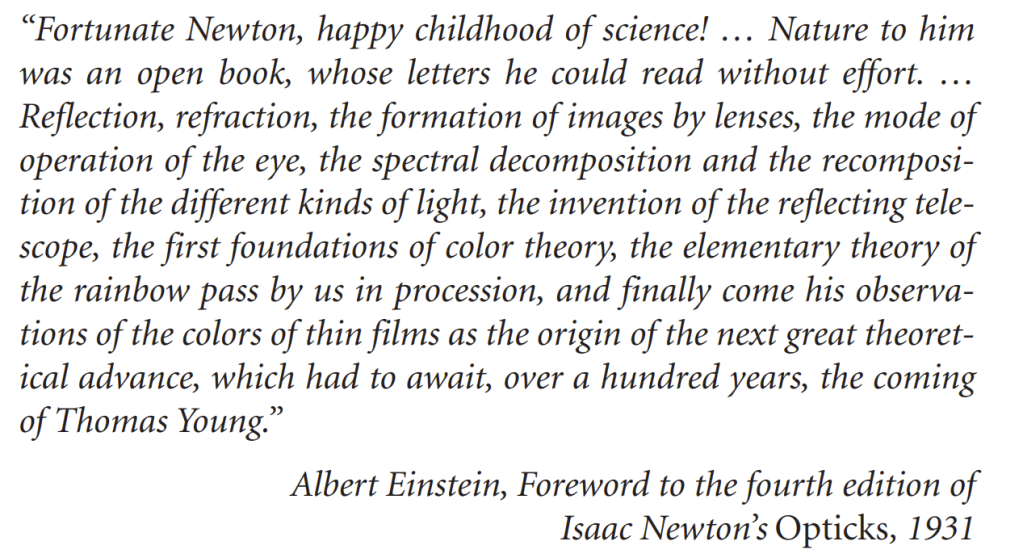

Einstein on Newton’s OPTICKS

Interesting that he ends the sentence with Thomas Young, who, in a way, disproved Newton’s corpuscular theory…

oh, how science evolves..

Recently, I came across a short but interesting book:

Bailyn, Bernard. On the Teaching and Writing of History: Responses to a Series of Questions. UPNE, 1994.

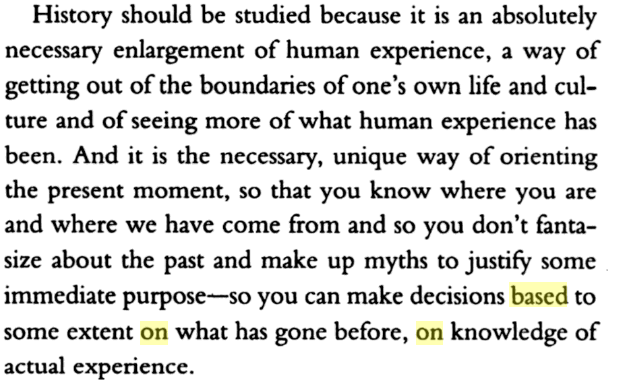

On page 12, there is an interesting discussion on why one should study history, both at the level of an individual and the collective. Below, I reproduce a paragraph related to this.

Oliver Heaviside

18 May 1850 – 3 February 1925

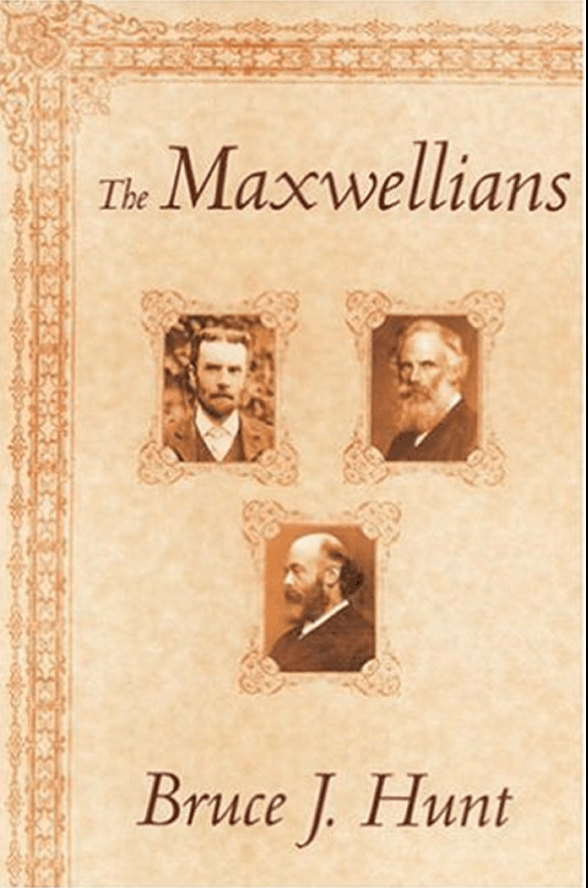

Among the books and discussion on this topic, I found this book by science historian Bruce Hunt to be very interesting. He identifies 3 plus 1 people who extensively developed Maxwell’s electromagnetic theory and presented in a way that the world could understand its significance. They were G. F. FitzGerald, Oliver Heaviside, Oliver Lodge and to a certain extent – Heinrich Hertz.

The foreword of this excellent book was written by a well known historian of science L. Peerce Williams and he sums the situation in which the theory was developed :

“Like Newton’s Principia, Maxwell’s Treatise did not immediately convince

the scientific community. The concepts in it were strange and the

mathematics was clumsy and involved. Most of the experimental basis

was drawn from the researches of Michael Faraday, whose results were

undeniable, but whose ideas seemed bizarre to the orthodox physicist.

The British had, more or less, become accustomed to Faraday’s “vision,”

but continental physicists, while accepting the new facts that poured

from his laboratory, rejected his conceptual structures. One of Maxwell’s

purposes in writing his treatise was to put Faraday’s ideas into the language

of mathematical physics precisely so that orthodox physicists

would be persuaded of their importance.

Maxwell died in 1879, midway through preparing a second edition of

the Treatise. At that time, he had convinced only a very few of his fellow

countrymen and none of his continental colleagues. That task now fell to

his disciples.

The story that Bruce Hunt tells in this volume is the story of the ways

in which Maxwell’s ideas were picked up in Great Britain, modified,

organized, and reworked mathematically so that the Treatise as a whole

and Maxwell’s concepts were clarified and made palatable, indeed irresistible,

to the physicists of the late nineteenth century. The men who

accomplished this, G. F. FitzGerald, Oliver Heaviside, Oliver Lodge, and

others, make up the group that Hunt calls the “Maxwellians.” Their relations

with one another and with Maxwell’s works make for a fascinating

study of the ways in which new and revolutionary scientific ideas move

from the periphery of scientific thought to the very center. In the process,

Professor Hunt also, by extensive use of manuscript sources, examines

the genesis of some of the more important ideas that fed into and

led to the scientific revolution of the twentieth century.“

Albert Abraham Michelson was a celebrated American experimental physicist. He was associated with one of the most famous experiments in physics : Michelson-Morley Experiment, which formed an important input for Einstein’s special theory of relativity.

Recently, I discussed about this experiment in one of my podcasts.

Michelson’s ability to design and develop optical instruments including the interferometer named after him, was one of vital elements in his legendary pursuit to measure velocity of light. He continued to refine this measurement over a period of 40 years or so.

He was also the first American to win a Nobel prize in science (physics, 1907). Americans adored him, and he shot up to fame with his ingenious experiments and became a folklore of United States.

There is a very nice historical account of the Michelson-Morley-Miller experiment in the book titled : The Ethereal Aether; a History of the Michelson-Morley-Miller Aether-Drift Experiments, 1880-1930. by Swenson, Loyd S. published in 1972.

(Yes, you read it right, there was another guy called Dayton Miller who played a critical role in refining the experiment initiated by Michelson and Morley )

In Swenson’s book, there are two stanzas from a poem by Edwin Herbert Lewis that highlights Michelson’s legend. Below I reproduce the same :

But in Kyerson rainbows murmur the music of heavenly things.

Is not this stranger than heaven that a man should hear around

The whole of earth and the half of heaven and see the shadow of sound?

He gathereth up the iris from the plunging of planet’s rim

With bright precision of fingers that Uriel envies him.

But when from the plunging planet he spread out a hand to feel

How fast the ether drifted back through flesh or stone or steel

The fine fiducial fingers felt no ethereal breath. They penciled the night in a cross of light and found it still as death.

Have the stars conspired against him? Do measurements only seem?

Are time and space but shadows enmeshed in a private dream?But dreaming or not, he measured. He made him a rainbow bar,

E.H. Lewis

And first he measured the measures of man, and then he measured a star.

Now tell us how long is the metre, lest fire should steal it away?

Ye shall fashion it new, immortal, of the crimson cadmium ray.

Now tell us how big is Antares, a spear-point in the night?

Four hundred million miles across a single point of light.

He has taught a world to measure. They read the furnace and gauge

By lines of the fringe of glory that knows nor aging nor age.

Now this is the law of Ryerson and this is the price of peace-

That men shall learn to measure or ever their strife shall cease.

Indeed humans shall learn to measure or ever their strife shall cease…

I recently read an interview of Lorraine Daston, a reputed historian of science on “Does Science Need History?”

She was interviewed by the philosopher Samuel Loncar

The long-form discussion is about history of science and how and why it is relevant not only to the public but also to the practicing scientists.

In the later part of the interview , I found an interesting and important observation made by Lorraine :

“One of the greatest achievements of science, contrary to what anyone would have thought not just circa 1700 but circa 1800, is the creation of the only effective international governance system that we have. In the face of two planetary crises—climate change and a global pandemic—it has not been the UN, it has not been the G8, that got together to diagnose the problem and suggest a solution. It has been the international community of scientists, and I would be extremely loath in any way to undermine the only example of semi-effective international governance we have.”

This is probably one of the important comments on science I have come across in recent times. In an age where nation-states are still fighting (big and small) wars, this is indeed a profound reminder on what truly is the instrument of effective (inter)national governance.

Do check out the whole interview. It has many interesting strands, branches and discussion including philosophy of science, publishing and some great references to explore.

As I have mentioned previously in my blogs, part of the reason why I blog is to bring out the human side of doing science. Interviews like these reinforces this thought, and encourages me as scientist to look into the history of science as not something decoupled from the science itself, but as a part of ones research in understanding why we, as human beings, are interested in science. In my opinion, our science education (and research) will be vastly enriched by including and emphasizing history of science as integral part of science. Frequently, I have also found that some of the best commentaries and criticism on science as human endeavor emnating from historians of science.

After all, it was history of science which opened our eyes towards understanding the structure of scientific revolutions. Hence Science + History —> better Science, and perhaps better human beings !