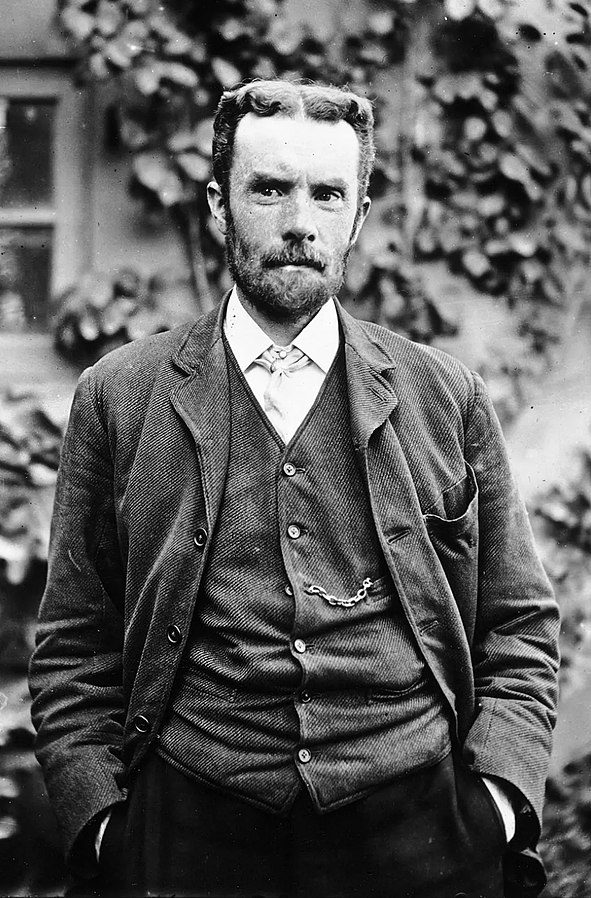

Oliver Heaviside

18 May 1850 – 3 February 1925

- I have been teaching Optics course this semester, and in order to introduce wave theory of light, I had to use Maxwell’s equation. In there, I mentioned that the expression for Maxwell’s equation that we use now is mainly thanks to the formulation of Oliver Heaviside.

- Born in 1850, Heaviside grew up in poverty and had physical illness in his childhood.

- Oliver Heaviside had an unusual life. He did not have a formal education in science or engineering, but contributed immensely to what is now called as classical electromagnetism.

- He was nephew of Wheatstone (of the fame of Wheatstone network), who helped him to find a job in a telegraph company, which was in 1870s, a booming industry.

- Heaviside showed a lot of promise in his work, and learnt a lot on the go.

- Around 1872, at the age of 22, he published his first research paper in Philosophical Magazine, which caught the attention of people such as Lord Kelvin and James Maxwell.

- At the age of 24, Heaviside quit his job (because of various reasons including ill health), and went back to live with his parents.

- Around 1873, Maxwell’s treatise on Electricity and Magnetism was published, and this mesmerized Heaviside.

- He studied it with dedication, but could not understand it. Therefore, he decided to re-write Maxwell’s treatise.

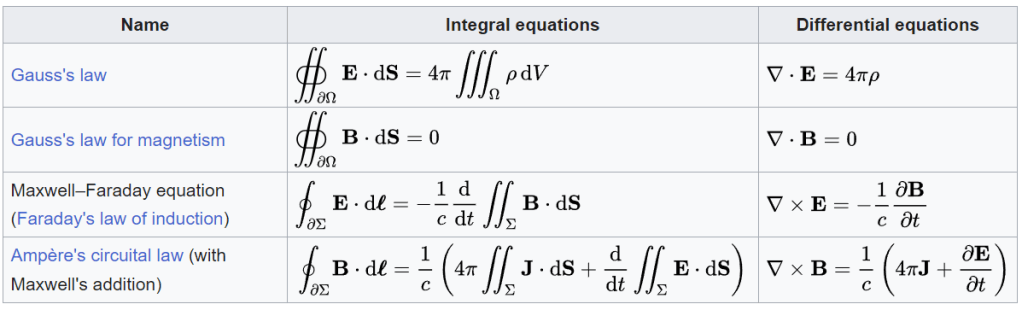

- Maxwell had used quaternion, which was a number system devised by Hamilton.

- This formulation was cumbersome, and was not easy to understand especially in the context of electricity and magnetism.

- Heaviside took this formulation, and re-casted it in terms of vector calculus.

- Interestingly, Gibbs had also done the same (earlier than Heaviside), but had not published his results.

- Nevertheless, both Heaviside and Gibbs pushed this formulation further, and eventually the research community saw its utility.

- There are many contributions of Heaviside towards electromagnetism, and inductive loading was one of them. Initially, this loading method of introducing repeated coils along the cable was met with a lot of opposition. But eventually, the advantage was realized and Oliver (and his brother, who initiated the work) were vindicated.

- Heaviside was a prolific researcher, and published 3 volumes on electromagnetic theory, in addition to various research papers.

- He also wrote a column spanning over 20 years in a magazine named The Electrician.

- After 1914 or so, Heaviside’s could not work due to ill health and paranoia, which disturbed his mind.

- In 1925, Oliver Heaviside passed away.

- There are some excellent books and biographical notes on Heaviside. Below are a few :

- Hunt, Bruce J. The Maxwellians. Cornell University Press, 1994.

- Hunt, Bruce J. “Oliver Heaviside: A First-Rate Oddity.” Physics Today 65, no. 11 (November 1, 2012): 48–54. https://doi.org/10.1063/PT.3.1788.

- Nahin, Paul J. Oliver Heaviside: The Life, Work, and Times of an Electrical Genius of the Victorian Age. Second Edition. Baltimore, Md: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002.

Among the books and discussion on this topic, I found this book by science historian Bruce Hunt to be very interesting. He identifies 3 plus 1 people who extensively developed Maxwell’s electromagnetic theory and presented in a way that the world could understand its significance. They were G. F. FitzGerald, Oliver Heaviside, Oliver Lodge and to a certain extent – Heinrich Hertz.

The foreword of this excellent book was written by a well known historian of science L. Peerce Williams and he sums the situation in which the theory was developed :

“Like Newton’s Principia, Maxwell’s Treatise did not immediately convince

the scientific community. The concepts in it were strange and the

mathematics was clumsy and involved. Most of the experimental basis

was drawn from the researches of Michael Faraday, whose results were

undeniable, but whose ideas seemed bizarre to the orthodox physicist.

The British had, more or less, become accustomed to Faraday’s “vision,”

but continental physicists, while accepting the new facts that poured

from his laboratory, rejected his conceptual structures. One of Maxwell’s

purposes in writing his treatise was to put Faraday’s ideas into the language

of mathematical physics precisely so that orthodox physicists

would be persuaded of their importance.

Maxwell died in 1879, midway through preparing a second edition of

the Treatise. At that time, he had convinced only a very few of his fellow

countrymen and none of his continental colleagues. That task now fell to

his disciples.

The story that Bruce Hunt tells in this volume is the story of the ways

in which Maxwell’s ideas were picked up in Great Britain, modified,

organized, and reworked mathematically so that the Treatise as a whole

and Maxwell’s concepts were clarified and made palatable, indeed irresistible,

to the physicists of the late nineteenth century. The men who

accomplished this, G. F. FitzGerald, Oliver Heaviside, Oliver Lodge, and

others, make up the group that Hunt calls the “Maxwellians.” Their relations

with one another and with Maxwell’s works make for a fascinating

study of the ways in which new and revolutionary scientific ideas move

from the periphery of scientific thought to the very center. In the process,

Professor Hunt also, by extensive use of manuscript sources, examines

the genesis of some of the more important ideas that fed into and

led to the scientific revolution of the twentieth century.“